This Article From Issue

January-February 2005

Volume 93, Number 1

DOI: 10.1511/2005.51.0

John James Audubon: The Making of an American. Richard Rhodes. x + 514 pp. Alfred A. Knopf, 2004. $30.

Under a Wild Sky: John James Audubon and the Making of The Birds of America. William Souder. xii + 367 pp. North Point Press, 2004. $25.

It has been 40 years since the publication of Alice Ford's classic biography of John James Audubon, and 15 years since the appearance of the revised edition, which added considerable information. Ford's carefully researched study provided readers with a detailed examination of Audubon's life and his artistic work. Building on Francis Herrick's idealized biography Audubon the Naturalist (1917), Ford made use of existing manuscript sources and her background as an art historian to construct a reliable biography that has been widely read and referenced ever since.

Given Audubon's iconic standing in studies of natural history and the environment, it is not surprising that the literature on him is substantial. His journals, letters and drawings have long been available, and in 1999 the Library of America published a 942-page volume of them. So one approaches any new book on Audubon with this question: What does it contribute that is new?

One of two biographies recently to arrive on the scene is John James Audubon: The Making of an American, by Pulitzer-prizewinning author Richard Rhodes, who is probably best known for his writings on technology and the atomic bomb. Readers of his earlier books will expect a well-crafted volume, and they will not be disappointed. In these pages, Audubon's life unfolds in an engaging manner, and the characters come to life.

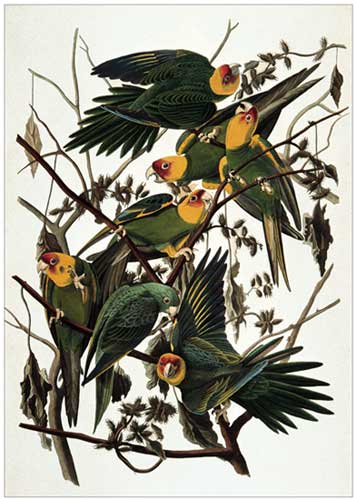

From John James Audubon: The Making of an American.

More important, as the subtitle suggests, Rhodes has as a backdrop for his story the narrative of American history. The result is a book that illuminates Audubon in a new way and uses his life to inform us about what it was like to live on the frontier in the years before the Civil War. For example, rather than dwelling on Audubon's feckless business ventures and the tired mythology that has grown up about his failures in that sphere, Rhodes explains the economic forces that benefited Audubon in his early married days and notes that he was just one of many people ruined in the Panic of 1819. Audubon, like many others in Kentucky, owned slaves. Rhodes comments on this fact and provides interesting background on many other details of life along the Ohio River. We learn, for example, that the log cabin Audubon lived in during part of his stay in Henderson, Kentucky, was built in a style (typical for the area) that had originated with Finns living near the Baltic and had been brought over (along with split-rail fencing) to the Delaware River Valley in the 1650s and then carried to Kentucky by Scotch-Irish pioneers.

Rhodes constructs a sympathetic portrait of Audubon and places him in his historical and cultural context. In addition, his book is replete with descriptions of Audubon's observations on birds and offers a detailed depiction of his evolution as an artist of avian life. Rhodes also gives readers some sense of the natural history community at the time, skillfully re-creating Audubon's interactions with many of the leading figures of the day. Ample quotations from Audubon's journals and letters animate the story. Rhodes also draws on various manuscript sources not used by Ford—for example, the extensive correspondence of Charles-Lucien Bonaparte, which is in the library of the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle in Paris. Historians of science as well as those interested in ornithology will find this book satisfying and enjoyable.

The other recent biography is William Souder's Under a Wild Sky: John James Audubon and the Making of The Birds of America. It has the unenviable fate of having to be compared with the biographies of both Rhodes and Ford. What distinguishes it from other studies is its attempt to place Audubon in the context of the development of American ornithology. Souder makes use of some of the literature on the history of natural history—for example, Charlotte Porter's 1986 study The Eagle's Nest: Natural History and American Ideas, 1812–1842, which tracks the relations of (and tension between) American and European naturalists.

From John James Audubon: The Making of an American.

Souder's book is a popular biography for the general reader. He initially takes as his theme the competition between Alexander Wilson (and his supporters) and Audubon. Indeed, the first third of the book is devoted largely to comparing the careers of the two men. Wilson began his American Ornithology with the goal of producing the first complete survey of American birds, and Souder focuses his attention on the divergent paths Wilson and Audubon pursued. Since Wilson died at an early age, the story is necessarily truncated.

In the rest of the book, Souder covers familiar ground, but in less detail and with less originality than either Rhodes or Ford. This is a less flattering portrait of Audubon than Rhodes's, perhaps because Souder accepts the myths that Audubon had poor business sense and was lazy when it came to doing anything other than wandering through forests.

The attempt by Souder to bring Audubon's life into the wider story of the rise of natural history has value. Historians of science may, however, become impatient with Souder's imperfect synopsis of that development and with his tendency to pursue tangents that do not advance the narrative. For example, Souder devotes almost a whole chapter to the 18th-century disagreement between Buffon and Thomas Jefferson over how animals in the New World compared in size with those in the Old World.

So a lack of space cannot be the reason that Souder gives scant attention to Audubon's artistic achievement. In his final chapter, he assesses The Birds of America by noting that Audubon depicted almost 200 more species of birds than did Wilson. That this famous work was perhaps the finest set of colored engravings using aquatint is not even mentioned, much less explored.

Because Souder's biography has less detail than Rhodes's and is more than 100 pages shorter, it may be attractive to readers who want a simple introduction to Audubon's life without extensive discussions of the birds he found so fascinating and the cultural context in which he operated. But for the reader who wants a richer treatment, one that goes beyond Ford's earlier biography, Rhodes's book is the better choice.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.