This Article From Issue

January-February 2019

Volume 107, Number 1

Page 54

Stories of major tech companies starting out in garages and dorm rooms are almost cliché now. These tales paint a picture of nerdy visionaries slaving away in front of blinking screens, living off pizza, and creating the technologies we now can’t live without. It can be difficult to imagine a world without a high-powered computer in your pocket, even for those of us who lived through it. But the history of computing reaches much farther back in time than these legends might lead us to believe. In The Computer Book, Simson L. Garfinkel and Rachel H. Grunspan trace the development of computers from the Sumerian abacus in 2500 BCE through the modern era and into the speculative future. Many of the stops along the way may surprise readers, such as the Mechanical Turk, whereas others, such as Boolean logic, seem so obvious that it’s hard to remember that they required invention. Many developments appear in the chronology much earlier than expected, such as an 1843 fax machine patent. In this excerpt, three milestones are highlighted: the Jacquard loom, the trackball, and social media’s role in the Arab Spring. Each of these milestones suggests possibilities beyond its original use and indicates ways that computers have become integrated into society. Garfinkel and Grunspan’s long view emphasizes how innovations built upon one another, particularly through open systems that allowed for improvisation and experimentation. It is through this innovation and exchange of information that the next generation of homegrown technologies will sprout from garages and dorm rooms around the world.

1801: The Jacquard Loom

Joseph-Marie Jacquard (1752–1834)

In 1801, French weaver Joseph-Marie Jacquard invented a way to accelerate and simplify the time-consuming, complex task of weaving fabric. His technique was the conceptual precursor to binary logic and programming that exists today.

Boris Pamakov; Wikimedia Foundation © Ad Meskens

Although looms of the 18th century could create complex patterns, doing so was an entirely manual affair, requiring an extraordinary amount of time, constant vigilance to avoid mistakes, and skilled hands—especially with intricate fabric patterns such as damask and brocade. Jacquard realized that despite the complexity of a pattern, the act of weaving was a repetitive process that could be carried out mechanically. His invention used a series of cards laced together in a continuous chain, with a row on each card where holes could be punched, corresponding with one row of the fabric pattern. Some cards had holes in the specified position, while others did not. Essentially, the punched cards were a control mechanism that contained data—like binary 0s and 1s—that directed a sequence of actions, in this case how a loom could be mechanized to weave a repeating pattern. A hole would cause a corresponding thread to be raised, while no hole would cause the thread to be lowered. The actual mechanism involved a rod that would either travel through the hole or be stopped by the card; each rod was linked to a hook, and together they formed the harness that controlled the position of the threads. After the threads were raised or lowered, the shuttle holding another roll of thread would zip from one side of the loom to the other, completing the weave. Then the rods in the holes would retract, the card would advance, and the process would start over again.

Jacquard’s invention evolved from earlier ideas by Jacques de Vaucanson (1709–1782), Jean-Baptiste Falcon, and Basile Bouchon, the last of whom invented a way to control a loom using perforated tape in 1725. Later inventors would take that concept and use punched cards to represent numerical data and other types of information.

1946: Trackball

Ralph Benjamin (b. 1922), Kenyon Taylor (1908–1986), Tom Cranston (c. 1920–2008), Fred Longstaff (dates unavailable)

The trackball was one of the first computer input devices to enable freeform cursor movement by the user, simultaneously over both the x- and y-axes on a computer screen. But there was a long time between its invention and its widespread use.

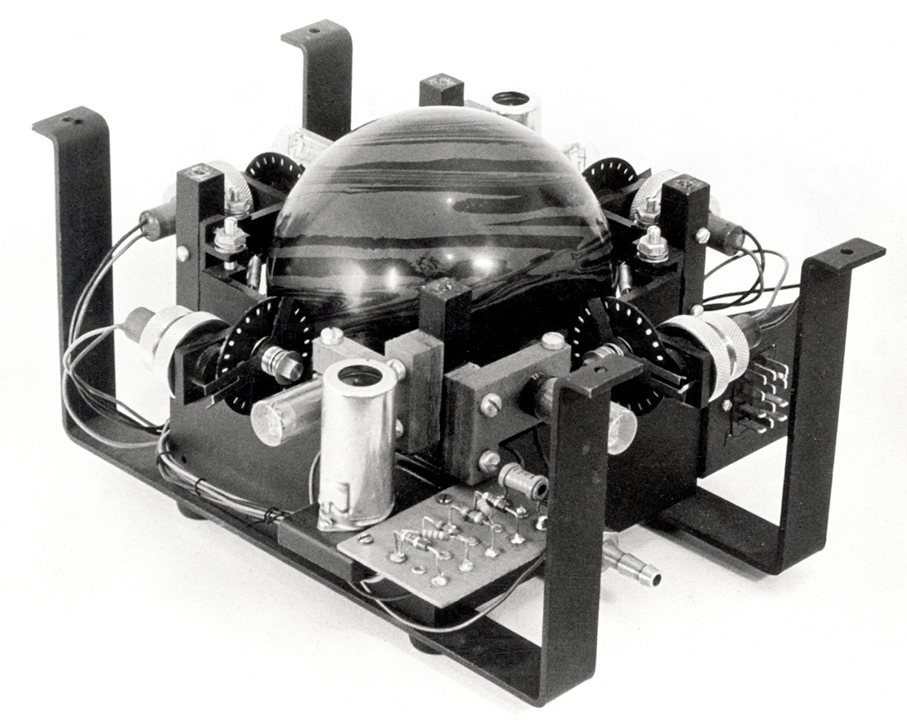

John Vardalas, IEEE History Committee

A British engineer named Ralph Benjamin designed the first prototype trackball while working on a radar project for the Royal Navy Scientific Service in 1946. The radar project was called the Comprehensive Display System and enabled ships to monitor low-flying aircraft on x and y coordinates using a joystick as the input device. Benjamin tried to improve upon this method of input with an invention he called the roller ball, which consisted of a metal casing containing a metal ball with two rubber wheels. It allowed users to control their onscreen movements with greater precision to input location data about a target’s aircraft. The British kept the device a military secret until 1947, when it was patented in Benjamin’s name and described as a device that correlated data between electronic storage and displays.

In 1952, Canadian engineers Tom Cranston, Fred Longstaff, and Kenyon Taylor built upon Benjamin’s concept and designed a trackball for the Royal Canadian Navy’s Digital Automated Tracking and Resolving (DATAR) system, a computerized battlefield information system. The design, based upon the Canadian five-pin bowling ball, allowed an operator to control and track the location of user input on the screen.

Benjamin’s roller ball eventually had a large influence on the development of the mouse and the modern trackball. The roller ball differed from the mouse in that it was a stationary object that was controlled by the user’s hand and fingers moving over it, rather than repositioning the entire device to different locations in physical space.

2011: Social Media Enables Arab Spring

Mohamed Bouazizi (1984–2011)

On December 17, 2010, a 26-year-old Tunisian street vendor named Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire in protest over the harassment and public humiliation he received at the hands of the local police for refusing to pay a bribe. Protests following the incident were recorded by participants’ cell phones. In the era of globally networked information systems, Bouazizi’s story spread much further than the people at the rally or Bouazizi’s family could have mustered on their own. After the video was uploaded to Facebook, it was shared and reshared across the social media sphere. The Facebook pages and the subsequent social media pathways the video appeared on were critical enablers that galvanized people to action on a scale they otherwise could not have achieved.

Alisdare Hickson

This incident is often cited as the catalyst for the Tunisian Revolution. Leveraging the digital diffusion capabilities of computer technology, including Facebook and Twitter, individuals and groups organized and coordinated real-world demonstrations, then posted the results for the world to see. The digital platform amplified and extended the emotional impact of these experiences to many others, who in turn shared the content even further.

Videos of protests might have been the spark that lit the uprising, but the pressure had been building since November 28, 2010, when allegedly leaked U.S. government cables that discussed the corruption of Tunisia’s ruling elites started circulating on the internet. The government of president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, who had been in office since 1987, fell on January 14, 2011, triggering demonstrations, coups, and civil wars elsewhere in northern Africa and the Middle East, in what is now known as the Arab Spring.

Immediate causalities of the Arab Spring included Egypt’s president, Hosni Mubarak, who was pushed out of office by a popular revolt on February 11, 2011, after nearly 30 years of authoritarian rule, and Libya’s ruler, Muammar Mohammed Abu Minyar Gaddafi, who had seized power in 1969 and was executed by rebels on October 20, 2011.

From The Computer Book: From the Abacus to Artificial Intelligence, 250 Milestones in the History of Computer Science. Copyright © 2018 by Techzpah LLC and published by Sterling. All rights reserved.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.