This Article From Issue

July-August 2002

Volume 90, Number 4

DOI: 10.1511/2002.27.0

Time Traveler: In Search of Dinosaurs and Ancient Mammals from Montana to Mongolia. Michael Novacek. x + 368 pp. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002. $26.

Ever since paleontology was established as a scientific discipline by Georges Cuvier near the end of the 18th century, its biggest advances have been driven by the discovery of unique fossils in the field. This is particularly true for the specialized branch of paleontology dealing with vertebrates, because animals such as dinosaurs and ground sloths tend to be preserved in far less abundance than clams and cycads. Instead of relying on faster microchips or better images from deep space, the most dramatic developments in paleontology still hinge on unearthing some amazing new specimen, often at a distant, exotic location.

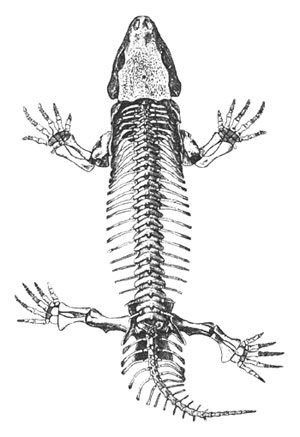

From Time Traveler.

In recent years, few scientists have racked up as many frequent-flier miles as Michael Novacek, who has circled the globe many times over in search of these elusive—yet critical—fossils. Somewhere between his duties as curator of paleontology, senior vice president and provost of science at the American Museum of Natural History and his multiple expeditions to fossil-bearing badlands around the planet, Novacek has found the time to write an autobiographical account of his experiences. The result is partly a travelogue, partly an adventure story, and partly an exposition on the important scientific achievements of Novacek and his team. Depending on which of these literary elements you find compelling, you may or may not be satisfied by the book.

Novacek begins with a highly personal account of his boyhood in suburban Los Angeles, where his father was a jazz guitarist and his mother worked as a cocktail waitress before devoting most of her attention to raising her children. Like many professional paleontologists, Novacek caught the fossil bug at an early age, becoming captivated by popular depictions of prehistoric creatures, such as the Tyrannosaurus rex that battles King Kong in the classic black-and-white film from the 1930s. He was lucky to live near such important fossil sites as the La Brea tar pits. His fascination with ancient life was also stoked by easy access to the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Family outings to collect fossil snails from road cuts in the Santa Monica Mountains presaged longer geological forays to the Grand Canyon.

Novacek's preadolescent enthusiasm for fossils barely survived what was apparently a fun-filled youth on the sunny beaches of southern California. The intellectual stimulation provided by fossils and deep time could compete for only so long with the multiple distractions of rock music, surfing and girls. This chapter of Novacek's life suggests that he might easily have ended up touring concert venues alongside Neil Young and other luminaries of the giddy 1970s music scene rather than launching a distinguished career in science. I couldn't help but wonder whether the foundations of his future success as a science administrator were laid during this carefree but intensely social stage of his development. Whatever else one might say about Michael Novacek, he is not—and apparently never has been—a science nerd.

Despite his subsequent history of wanderlust, most of Novacek's formative years were spent in the parochial confines of his native California. As an undergraduate at UCLA, he leapt at the chance to take part in his first genuine paleontological expeditions, under the tutelage of Peter Vaughn. We learn about the trials and tribulations of searching for Paleozoic vertebrates such as the fin-backed reptile Dimetrodon in the blistering deserts of southern New Mexico and the alpine heights of the Colorado Rockies. Along the way, Novacek gives us a primer on plate tectonics and the geological history of the Colorado Plateau.

The next port of call on Novacek's academic trajectory was San Diego State University, where he undertook a master's thesis under the supervision of Jason Lillegraven. Here he developed what would become a lifelong passion for fossil mammals. But instead of studying large, glamorous fossils like the saber-toothed cats and dire wolves he had known so well as a boy, he took an interest in tiny, nondescript fossil "vermin"—an epithet he applies to the hedgehogs and shrewlike beasts that flourished in the vicinity of San Diego some 40 to 45 million years ago. He also became an early convert to the emerging revolution in evolutionary biology known as cladistics.

For his doctoral degree, Novacek moved up the California coast to Berkeley, where he focused on another group of extinct vermin known as leptictids, whose central role in the evolution of modern groups of placental mammals has long been debated.

After a brief stint on the faculty of San Diego State, Novacek accepted a position at the institution he still calls home—the American Museum of Natural History in New York. There he found an outstanding group of colleagues, one of the world's most important and extensive fossil collections and the institutional infrastructure to conduct high-profile, wide-ranging fieldwork.

The rest of the book outlines Novacek's globetrotting exploits in Baja California, the Chilean Andes, Yemen, Mongolia and Argentina. The adventures he describes add an element of geographic and cultural diversity to the book, but at the risk of diluting his main scientific theme. There is little to unite an agenda of paleontological fieldwork in these disparate places, aside from the universal goal of recovering fossils that illuminate the complex history of life on Earth. For example, plate tectonics and biotic isolation have conspired to make the fossil record of South America interesting in its own right, but it cannot easily be related to the prehistoric menagerie Novacek's teams uncovered in Mongolia and Baja California. The problem is exacerbated by the fact that Novacek and his colleagues surge up and down the geological timescale, from deep in the Jurassic of Argentina to the Pleistocene and Neolithic of Yemen. Readers who want their popular science to have a clear focus may be confused and disappointed by these sudden leaps between continents and eras.

Novacek does an admirable job of putting a human face on the life of a field paleontologist. He paints realistic portraits of the constantly shifting political intrigue, the harsh climates and the logistical difficulties inherent in running expeditions in remote and inhospitable terrains. An obvious take-home message is that field paleontology can be dangerous work—Novacek recounts surviving a severed radial artery, a bout of heatstroke, a Giardia infection and a nearly fatal fall from a horse, among other life-threatening experiences. What makes any sane person go back to the field after such close encounters with death? It can only be the sheer joy of discovering another important piece in the most intriguing of all puzzles—the grand saga of how the myriad forms of life evolved.—Chris Beard, Vertebrate Paleontology, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.