A Walk to Remember

By Fenella Saunders

Preserved traces of a purposeful trip some 13,000 years ago say much about human and megafauna interactions.

Preserved traces of a purposeful trip some 13,000 years ago say much about human and megafauna interactions.

A unique set of footprints crosses what is now White Sands National Park in New Mexico. The tracks of one person headed in a straight line are closely paralleled by prints pointing the opposite way, indicating a return journey. The tracks suggest a quick pace, and slide around on the surface, as if it had been raining. And these tracks are at least 13,000 years old.

Establishing an age for footprints is notoriously difficult. Those that are discovered are usually at the surface, where there is little material to use in radiocarbon dating. But these prints present a vignette that may exist nowhere else in the world: The first set of prints are crossed by those of a mammoth and a giant ground sloth—and then the same human’s prints cross over the animal prints. Those creatures died out some 13,000 years ago, so the prints are at least that old. “At that point, we were justifiably excited, because that co-association let us build up a picture of humans living at a really great antiquity in the landscape along with extinct fauna,” explained paleontologist Sally Reynolds of Bournemouth University in the United Kingdom. ”That sort of insight into how ancient humans felt on their landscape in relation to the other fauna is something I don’t think you get from any other site in the world.”

Courtesy NPS/Bournemouth University

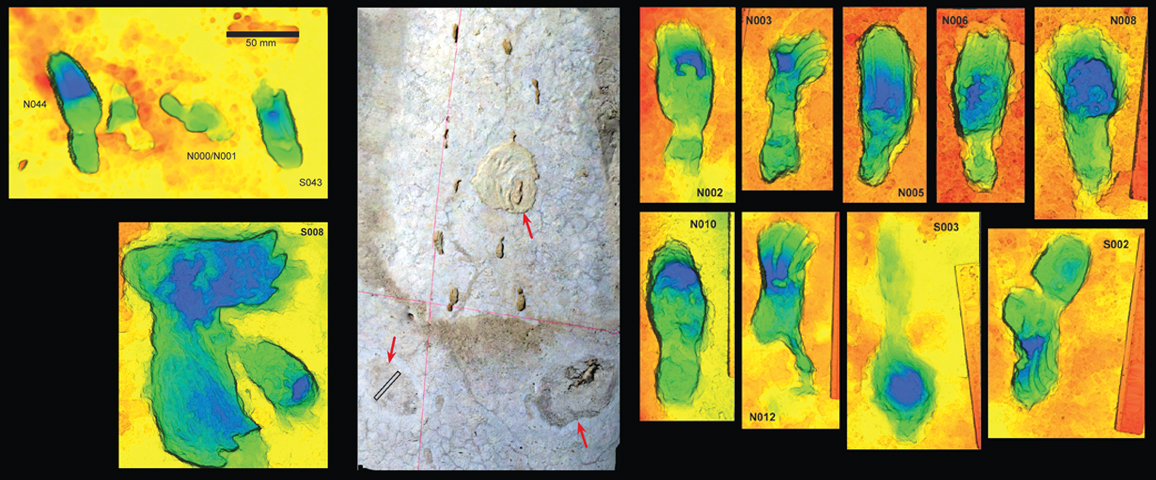

The track of more than 400 footprints was discovered in 2016 by Reynolds’s coauthor, David Bustos of White Sands National Park. The research team has since documented the prints using a method called structure from motion photogrammetry. Overlapping photographs taken around the item at oblique angles are used to create a three-dimensional model that can also determine depth and curvature of each footprint measured. “It’s very important that we have a permanent record of these tracks before they disappear forever, because once you excavate them, it’s a race against time, and they are essentially eroding in situ,” says Reynolds. “The photogrammetry is so much better than the more traditional ways of preserving the footprints, such as casting. The big, bulky casts sit in the museum gathering dust. We can share the 3D models digitally.”

Courtesy NPS/Bournemouth University

The models show an immense amount of variation among the prints, because of the slippery surface, but there’s little doubt that the prints all belong to one person, and the data show that they are the same coming and going. “I can’t say for sure that it wasn’t the twin of the person coming back,” quips Reynolds. “But the attributes of the person, the size of the foot and the height we can infer from that, and the walking style, are the same.” The measurements indicate the person was of the stature of a woman or an adolescent male. Along the path, a few child prints appear out of nowhere, so the person was carrying a toddler. But only in one direction—the variation in the load bearing on the footprints confirms that. “The little, tiny footprints are absent, and also there is slightly less marked asymmetry on the return journey than there is on the outward journey,” says Reynolds.

The site is also a rare opportunity to quantify how much prints from a single trackmaker can vary, but Reynolds laments that there are not sufficient standards for comparison. “Going forward, I do hope that we’ll get one or two more students who are interested in going out and mucking around on the beach or in the mud with wet feet,” she says, “in order to generate some interesting prints for us to look at.”

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.