This Article From Issue

November-December 2008

Volume 96, Number 6

Page 522

DOI: 10.1511/2008.75.522

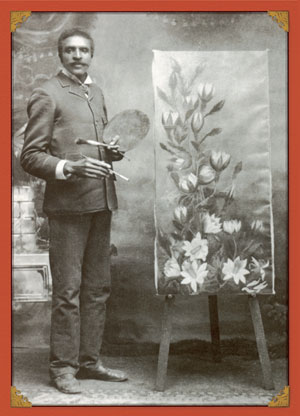

Horticulturist and inventor George Washington Carver's rough beginnings, his eventual higher education in racially tolerant Iowa, his delivery of "scientific farming" and its mantra of soil conservation to the Deep South, and, not least, sweet potatoes, soybeans and peanuts, and products made from them—it's all herein Tonya Bolden's George Washington Carver (Abrams, $18.95, ages 8 to 12). This latest entry in the fertile field of Carveriana stands out for its compilation of period paintings and documentary photos, artful design and layout, and the authority lent by Chicago's Field Museum, a partner in the publication.

From Tonya Bolden’s George Washington Carver

Bolden's storytelling pulls all of the pieces together into an eminently readable whole. She enlivens her story with quotes taken directly from primary sources. For example, in an 1896 letter recruiting young Carver to work at the Tuskegee Institute, Booker T. Washington says of his students there, "Words cannot fill stomachs. They need to learn how to plant and harvest crops." Tuskegee, Bolden tells us, was home to a journal called The Negro Farmer, in whose pages Carver excoriated "soil robbers" who failed to rotate crops.

Carver was deeply religious. He called his lab "God's little workshop," we learn, and he believed "that all of nature was God's creation." But Bolden doesn't tell us what he had to say about evolution.

Carver's status as an iconic scientist, the world-famous "Peanut Man," and a powerful example of how hard work and brilliance could combat deeply held racist beliefs in America are, of course, well known. But many readers are likely unaware of his artistic gifts. The book includes a few of his botanically themed paintings and drawings. He also dabbled in textiles and other media, including—go figure—peanut shells.

Many may also be surprised to learn that Carver had nothing to do with the invention of peanut butter. The idea that he did may be one of the most persistent urban legends—of the rural variety.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.