This Article From Issue

July-August 2010

Volume 98, Number 4

Page 348

DOI: 10.1511/2010.85.348

DREAMING OF SHEEP IN NAVAJO COUNTRY. Marsha Weisiger. Foreword by William Cronon. xxvi + 391 pp. University of Washington Press, 2009. $35.

The ongoing “debate” about global climate change demonstrates that many Americans distrust the explanations and predictions of environmental scientists. This lack of confidence may derive from any number of sources: economic interest, political persuasion, religious belief, class-based resentment, wishful thinking, emotionalism or ignorance. It is tempting to dismiss skeptics—especially those who question the reality of an environmental crisis and the need for science-based solutions—as irrational or stupid “denialists.” But that is too simple, too condescending. After all, scientists more than occasionally make mistakes and misuse data, and environmentalists habitually play the role of Cassandra.

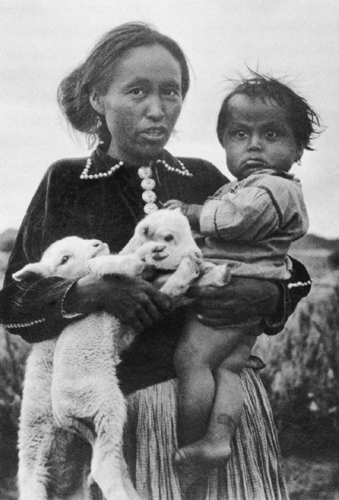

From Dreaming of Sheep in Navajo Country.

In Dreaming of Sheep in Navajo Country, a recent book about pastoralism among the Diné (as the Navajo people call themselves), Marsha Weisiger recounts a past example of scientists predicting an environmental catastrophe to a skeptical audience. Although this episode played out on the remote Colorado Plateau in the 1930s and early 1940s, it remains relevant today. The conflict over Navajo livestock fits into a historical pattern of well-meaning conservationists alienating potential allies—in this case, an indigenous group that cares deeply about the health of its land. Weisiger takes great pains to understand each side’s point of view, and her account deftly joins the cultural and the ecological.

Diné oral tradition says that sheep have existed since the beginning of the world, longer even than the Diné themselves. Historians have a different story to tell: They say that Navajos began herding livestock around A.D. 1700, after having both purchased and stolen domesticated animals from Spanish settlements on the Rio Grande. Navajos fully adopted pastoralism and transhumance—moving livestock from winter homes to summer pastures—in the second half of the 18th century, even as they abandoned their traditional homeland around the valley of the San Juan River, which was under siege from equestrian Utes. As they moved southward and westward, Navajos began traveling greater distances, both horizontally and vertically, during their seasonal migrations with their animals.

In the 1860s, during a period they refer to as the “Fearing Time,” most Navajos had to make a different, dreadful “Long Walk,” to a concentration camp run by the U.S. Army. Meanwhile, Kit Carson’s soldiers and enemy Utes slaughtered Diné flocks. After four years living as prisoners of war, the Diné returned home and rebuilt their herds, and by 1890 they had 1.6 million sheep and goats, according to federal agents. Classical ecologists would call this an ungulate irruption—an exponential increase in a population of hoofed herbivores that continues until it outgrows the carrying capacity of its range. Weisiger persuasively argues otherwise, showing that the rise and subsequent fall of the sheep population was more complex than that theoretical model allows.

Benefiting from a protein-rich diet, the Navajo population itself quintupled between 1870 and 1930—a phenomenal success story, given that this was the period during which the overall population of Native Americans in the United States reached its all-time low. At the onset of the Great Depression, some 39,000 Navajos and about three-quarters of a million stock animals lived on a reservation comparable in size to West Virginia. But the land—Diné Bikéyah, or Navajo Country—bore clear signs of environmental distress, including gullies, sand dunes and parched stubble.

U.S. officials looked at range conditions with alarm. Boulder (Hoover) Dam was nearing completion, and the government did not want the reservoir behind it to fill up with silt from the upstream Navajo Reservation. A study of erosion on the reservation was undertaken in 1933. Federal scientists—range technicians, soil specialists, engineers, agronomists and biologists—gravitated to a simple, single-cause explanation for soil damage: Navajos owned too many animals. In their unregulated herding, they had exceeded the land’s carrying capacity. New Deal officials dismissed a competing theory put forward by geologists and hydrologists that emphasized drought cycles. The New Dealers didn’t have any baseline data, but they held strong assumptions about historical conditions. They believed that the land had once been green and lush, that it had been degraded by overgrazing, and that, through herd reduction and proper management, it could be returned to its “natural” climax condition. Influenced by the ideas of ecologist Frederic Clements, range scientists felt confident they could restore the balance of nature.

Under the leadership of John Collier, an appointee of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) instituted a herd reduction program in 1933 that lasted through the mid-1940s. Initially Collier secured the cooperation of Navajo leaders, who recognized that something had to be done to improve range conditions. Collier yoked the reduction of livestock to the expansion of tribal domain into the “Checkerboard” area of western New Mexico. Historically part of Diné Bikéyah, the Checkerboard was riddled with the inholdings of Anglo and Hispanic ranchers. Although Collier convinced Congress to extend the Arizona boundaries of the Navajo Reservation, a similar bill for New Mexico stalled. Despite this failure, the BIA pushed ahead with the reduction program; over the course of a decade, Navajos lost about half of their animals. And the program became progressively more coercive, an outcome that pained Collier. Despite his paternalism, he was an enlightened reformer who sincerely wanted the Navajo Nation to have greater power and autonomy.

In the eyes of the Diné, Collier became an evildoer. Traumatized Navajos had a dramatically different interpretation of past range conditions: Diné Bikéyah had indeed once been green and lush, they said. It only changed when the government introduced spiritual chaos by killing and wasting animals. This sacrilege made the land unhealthy. Only Navajo ceremonies like the Blessingway could restore balance. Then the rains would return, and dormant plants revive.

Who was right? According to Weisiger, whose history of the conflict is definitive, each side got some things right and some things wrong. As we now know from tree-ring data, climate change did in fact set the stage for range deterioration. The Southwest experienced a decades-long dry spell in the late 19th century, which was capped by an extreme drought that lasted from 1899 until 1904, followed by an unusually wet period ending in 1920. This dry-then-wet pattern encouraged arroyo erosion and sand-dune formation—a geomorphologic cycle that had happened many times before in this sandstone-dominated landscape.

Erosion was natural. However, it was accelerated, intensified and expanded by Navajo land use. By keeping large numbers of horses, goats, sheep and cattle—each of which ate a different part of the plant spectrum—Navajo herders had a comprehensive impact on the range. Government scientists’ idea that flocks should be reduced was a good one. And yet range conditions—and social conditions—only got worse in the wake of livestock reduction. Science failed to heal the land. At some point the reservation reached an ecological tipping point. In the second half of the 20th century, invasive Bromus tectorum (downy brome or cheatgrass) came to dominate some areas of the Navajo range.

What went wrong? A combination of bad luck, incompetence and arrogance doomed a well-intentioned program. Instead of encouraging home consumption of livestock—or communal feasting in the form of Blessingway ceremonies—the government decided to remove excess animals by railroad and outsource the killing to slaughterhouses. But when the main cannery couldn’t handle the massive number of goats, the government maintained its reduction schedule the only way it could: Reservation agents shot thousands of animals in place and left them to rot. When the government compensated Navajos, it did so based on a calculation of animals’ value on the free market rather than taking into account their full economic value on the reservation. And their cultural value wasn’t even considered. Diné men owned prodigious numbers of horses as markers of status and masculinity. To outsiders, such nonworking animals had zero worth. New Dealers instructed Navajo men and women to think of their cultural property as “animal units” and dollars.

Weisiger’s analysis of the conflict is the first to explain the interplay of gender and ecology. Government officials, all of them men, negotiated (in English) exclusively with Navajo men, whom they assumed were heads of households. But Diné society was in fact matrilineal and matricentered—and far more egalitarian than New Deal officials recognized. Traditionally, migration and residence patterns followed kinship structures. New Dealers wanted to end the large seasonal movements of matricentered families; they wanted to transform Navajos from transhumant nomads to landed ranchers who practiced soil conservation. To do this, the government divided the reservation into numerous fenced-in districts under the joint responsibility of male heads of household—a masculinized model of ranching.

Diné women bore the brunt of livestock reduction and were especially hurt by the government’s sheep and goat programs. Women and girls owned virtually all of the goats, a symbol of femininity, and they owned many more sheep than did men (men owned more cattle and many more horses). Girls had primary responsibility for herding sheep. They used the long-haired wool from the multicolored Navajo-Churro sheep to weave blankets—a major export item. But the government considered the breed to be low in value and genetically degenerate. They introduced “improved breeds” that promised more meat and more commercial-grade white wool, and they nearly eradicated the churras. Only belatedly did policy makers acknowledge that the native breed was better suited to the semiarid environment and produced superior wool for hand-weaving. For years government scientists tried to breed a hybrid sheep, without success. U.S. officials failed to consider the obvious solution: Let the Navajos have two breeds of sheep, one for market and one for weaving.

New Dealers hoped to prevent what would later be dubbed “the tragedy of the commons.” They didn’t discern that the bounded land-use rights of existing matrilineal kinship groups prevented free-for-all grazing. The logic of enclosed grazing districts seemed irrational to Navajos, who treated the land itself as communal property. In a contradictory double blow, the government also undercut the Navajo tradition of private ownership of animals. The government mandated a small maximum herd size for all Diné, thus reducing everyone, including wealthy herders, to subsistence level. The irony of this radical experiment in social engineering is astounding. After working for decades to privatize the communal economies of Indian tribes, the United States forced a crypto-communistic program down the throats of an indigenous group.

After initially supporting livestock reduction, Navajos began to resist—not through violence but by employing the all-American instruments of votes and petitions—and they eventually forced the government to abandon its program. In the 1950s, the Diné even enlarged their flocks modestly. By that point, however, the tribal economy was in ruins. Unemployment, indebtedness, poverty and alcoholism ravaged Diné Bikéyah. As time passed, the collective memory of the reduction program gained mythic status. Among reservation Navajos, a complex history became a simplistic story: John Collier had sickened the land by making it run red with the blood of Navajo flocks. According to Weisiger, “many experienced stock reduction as genocidal” because of their past trouble with the United States and because of their ceremonial understanding of livestock. To this day, Navajos remain suspicious of scientific land management—even when the directives come from their own tribal council. The range remains degraded.

Like the Comanches of the Southern Plains, who overhunted bison after acquiring horses, the Navajos overextended their animal economy. Had they enjoyed more time and space, these indigenous peoples might have self-corrected. Successful transhumant herders such as the Masai developed their techniques over thousands, not hundreds, of years. The restless expansion of the United States and its settlers removed this luxury of time. Only one option remained: Navajos and federal scientists had to work together to bridge the gap between “religious” and “rational” approaches to land management. This should not have been so difficult. As Weisiger points out, “both the Diné and the New Dealers believed in the so-called balance of nature, which one called hózhó? and the other called equilibrium.” Navajos had “faith in ceremony,” whereas scientists had “belief in the doctrine of carrying capacity.” Both groups believed in the power of humans to shape nature for good or ill, and both wanted the same thing: to restore the land to good health. Tragically, this common ground eroded into distrust. Weisiger, an unusually fair and empathetic historian, faults Navajos for their “intransigence” and “deep denial.” Yet she is “not convinced that faith precluded pragmatic problem-solving.” She reserves special blame for conservationists, who treated Indians as superstitious, irrational antagonists rather than as partners with a shared goal. Surely there is a lesson here for the present day.

Jared Farmer, a member of the history department at Stony Brook University, is the author of Glen Canyon Dammed: Inventing Lake Powell and the Canyon Country (University of Arizona Press, 1999) and On Zion’s Mount: Mormons, Indians, and the American Landscape (Harvard University Press, 2008).

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.