This Article From Issue

November-December 2025

Volume 113, Number 6

Page 322

It seems amazing that it has been a century since the trial of The State of Tennessee v. John Thomas Scopes, yet the central question of what constitutes evidence-based science still remains under debate.

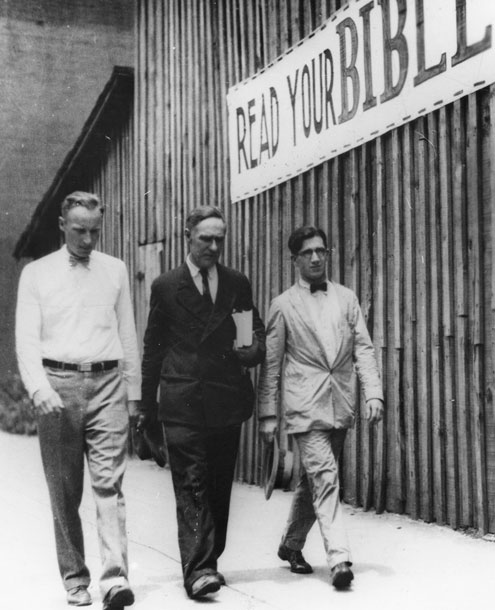

Scopes (shown below, right, with attorneys) was found guilty in that trial of violating Tennessee’s Butler Act, which forbade the teaching of any theory that contradicted the Biblical story of the divine creation of humans. Scopes was fined, but his verdict was overturned on a technicality. The Butler Act was not repealed until 1967, and the Supreme Court ruled other state laws against the teaching of evolution to be unconstitutional in 1968.

Bryan College

However, as Robert T. Pennock details in this issue’s Science and Engineering Values column, On a Wing and a Prayer?, court cases continued. Pennock was an expert witness in the Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District trial that concluded in 2005. That case centered on intelligent design, which proponents tried to argue in court was different from creationism. Pennock recounts how he and other expert witnesses were able to show that an intelligent design textbook that was central to the court case switched from using the terms “creationism” and “creationist” to “intelligent design” after a 1987 Supreme Court case ruled that teaching creationism as science was unconstitutional. In the Dover case, the judge also ruled that intelligent design could not be taught as science.

Pennock uses the example of aerospace engineering to highlight the point that including the divine in any evidence- based enterprise would be irresponsible. But as he notes, there’s nothing about evolution that precludes a life of meaning and purpose. Indeed, although scientific research can be tough, most scientists find that their work is fulfilling, no matter what their personal convictions may be.

Scientists continue to show dedication to their research, despite significant ongoing U.S. federal funding cuts. Communication has always been central to the scientific process, and scientists have been looking for ways to make clear how these cuts will affect research. For several issues, we have been requesting letters from scientists to raise awareness as to why their research is important. There are more responses in this issue’s Letters section, and we are consistently impressed by the research and dedication of the scientists who write in. We encourage you to continue submitting your letters. As a reminder, please keep your letter submissions to no more than 300 words. Let us know if you would like us to keep your letter anonymous, or if you are comfortable sharing your name, your location, or both. Please note that as a nonprofit, American Scientist is not permitted to endorse any specific legislation or candidate, but we can support evidence-based science policy, so please keep your submissions nonpartisan. Focus your letter on why your work is important, effective, and worth carrying out. Send your submissions to editors at amscionline dot org with the subject line “Science Is Important.” Letters may be published in print or on our website, and may also be featured on social media.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.