Celebrate Indie Bookstore Day with 6 Books from Indie Publishers

By Dianne Timblin

To celebrate Independent Bookstore Day we couldn't resist recommending some reads worth seeking out (or ordering from) your favorite independent bookstore. And as usual, our celebration here at Science Culture comes with a twist: We're going all-indie today, focusing specifically on science, math, and tech books issued by independent publishers—truly the unsung (and occasionally unpaid) heroes of the book-producing world. Culled from a long and worthy list, here are six recommendations for the day.

May 2, 2015

Science Culture Communications Review Scientists Nightstand

If you love books and independent bookstores as much as we do here at Science Culture Central, you’re in luck. We’re all going to have a pretty great day. Why? It’s Independent Bookstore Day!

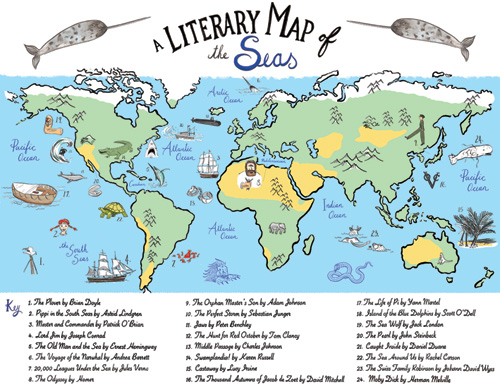

The first annual Indie Bookstore Day took place in California last year and was such a rousing success that the event has gone nationwide: Today 400 stores are participating. In addition to their usual hardback and paperback wares, many will offer items designed to celebrate the day, such as the Literary Map of the Seas shown above; tote bags decorated by cartoonist Roz Chast; a set of books about books, packaged together in a tin box; and tea towels featuring literary quotes (one set is “sweet,” the other, “salty”). If your Facebook and Twitter feeds aren’t already overrunning with what’s in store today in your area, here’s a handy city-by-city roundup of indie bookstore goings-on. If your city isn’t listed, this mapcan help you locate an independent bookstore so you can find out for yourself. You can also follow ongoing developments on Twitter with the hashtag #bookstoreday, or by checking out the Independent Bookstore Day Twitter page.

To mark the occasion, we couldn’t resist the idea of recommending some STEM-related reads worth seeking out (or ordering from) your favorite independent bookstore. But as usual, our celebration here at Science Culture comes with a twist: We’re going all-indie today, focusing specifically on science, math, and tech books issued by independent publishers—truly the unsung (and occasionally unpaid) heroes of the book-producing world.

There are so many great choices that this list could easily reel on and on. But for our purposes today we’ve narrowed it down to six.

6 Indie Press Books for Indie Bookstore Day

Ada’s Algorithm: How Lord Byron’s Daughter Ada Lovelace Launched the Digital Age, by James Essinger. Melville House, 2014. $25.95.

James Essinger, who previously authored the well-received Jacquard’s Web, takes up the story of Ada Lovelace, born into scandal as the daughter of poet Lord Byron, yet for many years a forgotten collaborator of Charles Babbage, who was widely credited with inventing the computer. In recent years Lovelace has become something of a darling of the Internet age; Essinger reminds us of the good reasons why. He makes the case that the computer era could have begun in the 1800s had Lovelace’s work been studied seriously in her own time. Given the 19th century’s estimation of women’s abilities, however, it wasn’t to be. Her own tutor wrote to Lovelace’s mother of his concern about the “strain” of her studies: “The very great tension of mind which [advanced mathematical problems] require is beyond the strength of a woman’s physical power of application. Lady L has unquestionably as much power as would require all the strength of a man’s constitution to bear the fatigue of thought to which it will unquestionably lead her.” (I feel a bit exhausted just reading that evaluation, although for entirely different reasons.) Essinger is a terrific storyteller, and he knows a great story when he sees it. Ada’s Algorithm is a riveting read.

Beautiful Birds, by Jean Roussen and Emmanuelle Walker. Flying Eye Books, 2015. $19.95.

We could happily assemble a list composed of fabulous children’s books from independent publishers, but today we’re sneaking just one book for young readers into this list that’s otherwise for grown-ups. Its title doesn’t lie: These birds are beautiful. Emmanuelle Walker’s illustrations are mesmerizing—every page is drenched in color, lit with whimsy, and composed by a sure hand. Jean Roussen’s text is lilting, relaxed, and never cloying. An alphabet book geared for kids five to seven years old, the structure allows Roussen and Walker to feature a variety of birds from all over the world. From kakapos to flamingos, there’s much to enjoy here.

I, Little Asylum, Emmanuelle Guattari (translated by E. C. Belli). Semiotext(e), 2014. $9.95.

This is a book of beautiful between-nesses: It rides a line between poetry and prose, history and memoir, fiction and nonfiction. It depicts life at an inpatient psychiatric facility that became famous as an experiment in communal living; with its founding in 1951, La Borde drew together patients, their caregivers, and their caregivers’ families. We’ve recommended this haunting, finely wrought book before (in our holiday gift guide), so if you haven’t looked it up yet, do check it out. It’s a bit of a hidden gem and well worth requesting if your bookstore doesn’t have it on hand.

On Immunity: An Inoculation, by Eula Biss. Graywolf Press, 2014. $24.00.

Having previously authored books on family and race, Eula Biss’s role as a new mother led her to consider the nature of parental fear and its effect on both the individual and the community. Taking up the subject of vaccination, Biss thoughtfully examines its history, its metaphorical weight, and the underlying science—as well as how and why vaccination has come to the fore of contemporary cultural and parenting debates. As reviewer Katie L. Burke notes, “The anti-vaccination movement has a long history, one that has been rekindled in the last decade by a 1998 study linking measles-mumps-rubella vaccination to autism—a study later found to be based on data fabricated in response to a lawyer’s bribe. Although vaccinations are known to prevent disease, no one can be 100 percent sure that they will not harm some recipients. . . . We fear the unknown, and those fears are shaped by our experiences and culture.” In On Immunity, Biss wisely places her meditation on vaccination at the center of all these influences, finding, in Burke's words, “the common ground underlying the full range of individual decisions. In so doing, she gets beyond the polarizing debate and to the heart of what we are really trying to talk about.” (For more about this book, check out Burke’s full review.)

Most Wanted Particle: The Inside Story of the Hunt for the Higgs, the Heart of the Future of Physics, by Jon Butterworth. The Experiment, 2015. $24.95.

Author Jon Butterworth, a physicist working at the Large Hadron Collider, provides an inside account of the experiments leading up to the discovery of the Higgs boson. Equally intriguing, the book’s final chapter discusses what’s next, particularly because the Standard Model of particle physics doesn’t represent the whole story. (If you’re interested in sampling a bit of the story before jumping into the book, check out an excerpt from our March–April issue.)

Thank you, Madagascar: The Conservation Diaries of Alison Jolly, by Alison Jolly. Zed, 2015. $27.95.

If you’ve ever wanted to experience the flora and fauna of Madagascar, Alison Jolly’s diaries may be the next best thing to being there. A primatologist whose field research on lemurs upended the notion that males were dominant in all primate species (her behavioral studies published in the 1960s showed otherwise), Jolly had a deep appreciation for the remarkable biodiversity of Madagascar and a nuanced understanding of the island’s political and cultural complexities. Weaving together diary entries representing decades of research trips to Madagascar, Jolly brings this world into sharp focus. She helps readers follow connections of all kinds threading through events related to the research, and when she tells of unforeseen consequences that arise from the researchers’ presence, such as a young guide’s death resulting from payment he receives for the work, she quietly and matter-of-factly breaks your heart.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.