2020's Most Popular Blog Posts

By The Editors

The most popular 2020 blog posts on our website.

January 6, 2021

From The Staff Communications

In compiling a top-10 list of this year’s most popular blog posts on American Scientist's website, we decided to look at what you—our readers—have been searching for the most. So here they are!

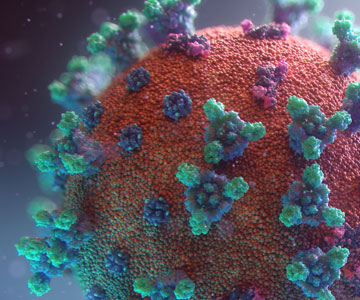

10. COVID-19 Is Inspiring Innovation

by Aranka Anema

Advancements are sparked from new collaborations in science and business during the pandemic.

(The Long View — MAY 8, 2020)

9. What COVID-19 Misinformation Says About All of Us

Coronavirus myths reveal ourselves—our hopes, dreams, and fears. When someone shares such falsehoods, we should at least listen to their needs.

(The Long View — June 9, 2020)

8. Like an Afterburner

Updating the theoretical model for the solar wind took years, new data, and kindness.

(The Long View — September 15, 2020)

7. More Testing, Faster Testing

More types of tests for the coronavirus are becoming available, but how do we know which to use when?

(From The Staff — October 12, 2020)

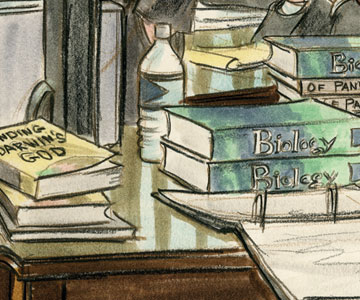

6. Books on Innovation and Imagination

by Flora Taylor

5. Did Intelligent Design Just Miss Its Corona Moment?

by Adam Shapiro

Proponents could have demonstrated the apolitical nature of their claim if they had debunked the Chinese lab myth using their methods. Instead, they have doubled down against Darwin.

(Macroscope — July 16, 2020)

4. The Dangerous Resurgence in Race Science

by Adam Shapiro

Bret Stephens’s recent New York Times column on “Jewish genius” is another example of how pseudoscientific claims about race and intelligence extend the history of eugenics into the present day.

(Macroscope — January 29, 2020)

3. Optimal Conditions for Viral Transmission

Everyone is concerned about spreading the novel coronavirus, but what variables actually affect its survival?

(Macroscope — April 3, 2020)

2. Science Book Gift Guide 2020

by The Editors

STEM-related books for any season

(Science Culture — December 4, 2020)

1. Making a Medical Face Mask at Home

Staff members reviewed the process of making and comfort of wearing several homemade face mask designs.

(From The Staff — August 10, 2020)

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.