This Article From Issue

November-December 2020

Volume 108, Number 6

Page 326

Here’s a shorthand way to think of my research: Using bugs as drugs may one day bring hope to soaps.

I am an allergy and immunology physician who explores the intersection of the microbiome, the skin, and the environment to identify why allergic diseases have become more common in modern times

All our scrapes, scratches, scrubbing, and soaps take a toll on our skin. The natural oils that our skin makes are part of the normal processes the skin uses to repair itself after these insults.

Patients with atopic dermatitis, more commonly known as eczema, suffer from dry, itchy skin and rashes, and they have a higher risk of developing hay fever, asthma, and food allergies. The cause of eczema is still unknown, but studies completed by my team and others continue to suggest that manipulating the skin microbiome—the community of all the bacteria and other microorganisms living on the surface of the skin—may offer therapeutic benefits to patients.

Ian Myles

My colleagues and I hypothesized that if we directly sprayed live bacteria named Roseomonas mucosa—a naturally occurring skin microbe—on the skin of patients with eczema, those healthy bacteria might make for healthy skin. In a recent paper in Science Translation Medicine, we reported on the success of early trials for this therapy

Using human cells and mice, we were able to uncover additional evidence that oils from bacteria that reside on the skin may also play a role in skin health. The oils from Roseomonas induce a specific skin repair pathway, in part by influencing molecules that are more frequently associated with our nerves than with our skin. These oils also help kill Staphylococcus aureus, a bacteria known to make eczema worse.

What Do Patients Want?

Our hope is that a topical treatment using Roseomonas bacteria will be an improvement over current eczema treatments.

In 2013, the U.S. Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) began soliciting direct input from patients and patient advocacy groups through events

known as Patient-Focused Drug Development meetings (PFDD).

In September 2019, the FDA conducted a PFDD for eczema. One of the

major findings was that itching was the

symptom of primary concern for patients and their families. This response

stands in contrast with the FDA’s current practice of approving new drugs

based solely on improvement in how

the rash looks, instead of how the rash

feels. Patients also reported a high rate

of complications from their current

treatments and expressed particular

concerns about using topical steroids.

Overall, patients said that eczema

substantially decreased their quality

of life because of the need to apply

medications frequently. Eczema also

drained their emotions and deprived

them of sleep due to unmanageable

itching in either them or their children.

A Treatment or a Cure

Two years ago, my colleagues and I reported our results from a study that followed 15 participants with eczema: 10 adults as well as five children over the age of nine. Because eczema most often afflicts children who are younger than seven, our newest study enrolled an additional 15 children as young as three years old. Overall, our patients achieved a 60 percent to 75 percent improvement in their rash and itch by applying Roseomonas two to three times per week for four months.

Patients and their families also reported needing to apply topical steroids less often and a better quality of life as they slept more and itched less. One patient complained of mild itching during the minute or so it took the spray to dry on their arms, but there were no other complaints related to treatment. Thus, taken together with some of our safety studies in mice, Roseomonas continues to appear safe.

Ian Myles

One of the more promising findings of our new study was that patients’

symptoms improved for up to eight

months after stopping the bacterial

spray medication. The advantage of

using live bacteria is that the microbes

can take up residence on the skin. We

found that the bacteria lived on the

skin at least eight months after treatment and likely continued to provide

clinical benefit without the need for

constant application.

Although not cured, many patients in the study described their symptoms as “muted.” Their typical day was better than usual, and although eczema flares still occurred, they were less frequent and less severe. Theoretically, applying our treatment as soon as symptoms manifest might prevent future disease and thus be “curative”— however, for now such thinking is speculation.

Even if Roseomonas is more treatment than cure, our findings are still directly aligned with the goals laid out in the PFDD: “sustained relief from itch,” a reduced need for topical steroids, and an overall improved ability to “go about daily life.”

What Comes Next?

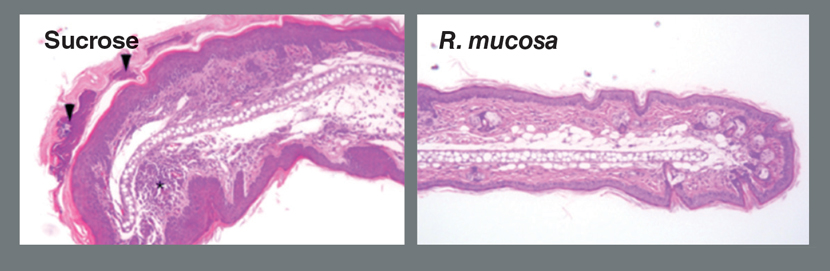

We are expanding our clinical Roseomonas study to include many more patients in a placebo-controlled trial. In

the new clinical study we are starting,

half of the 120 or more patients that enroll will get our Roseomonas spray, and

the other half will receive only a sugar

water spray

The knowledge that bacteria such as

Roseomonas can help patients with eczema will also allow us to examine which

environmental exposures might harm

these microbes. According to a 2016 report from the Environmental Protection Agency, there are more than 8,700

chemicals on the U.S. market. Not all of

these are common and not all are used

on the skin, but the number of possible

combinations and concentrations of

chemicals we expose our skin to on a

daily basis could be nearly infinite.

By systematically evaluating which

exposures help, which hurt, and which

are benign, we may be able to “bathe

smarter” and identify the best way

to keep ourselves clean, without disrupting the balance of the bacteria that

keep us healthy.

This article is adapted from a version that appeared in The Conversation (http://theconversation.com).

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.