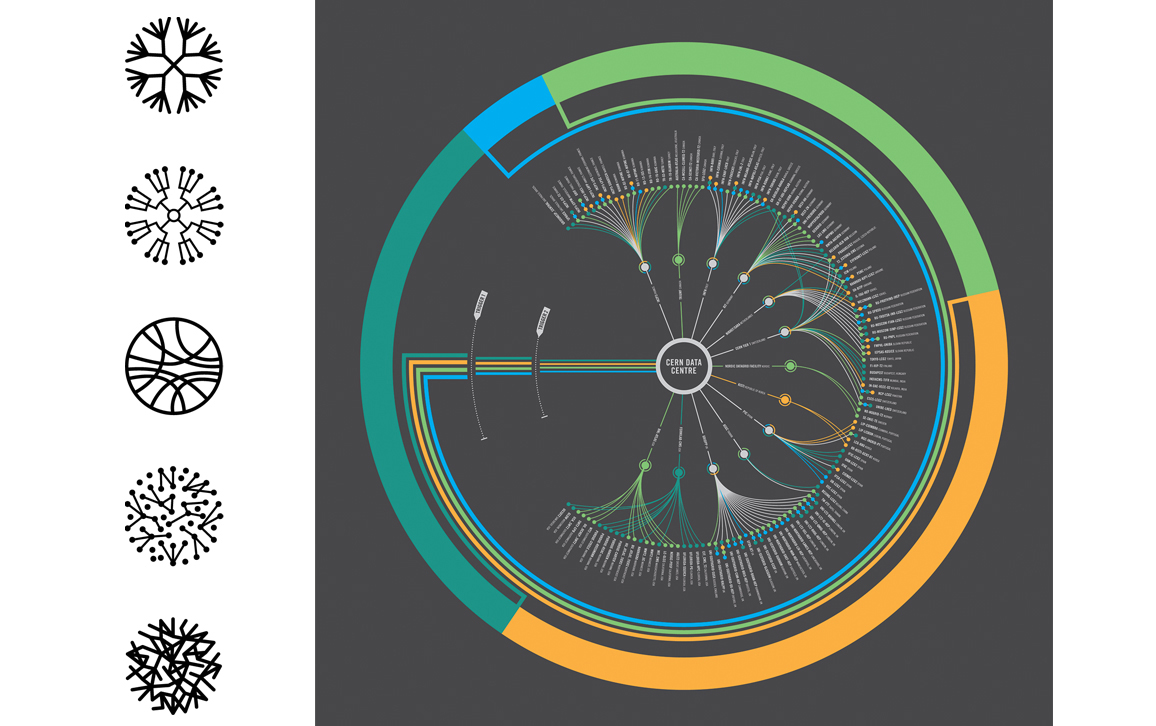

Circular Visualizations

By Manuel Lima

A radial layout continues to dominate visual expressions of information and data.

A radial layout continues to dominate visual expressions of information and data.

It was February 2011, I had just finished giving a lecture, and one professor stood up and asked, “Why do most of the visualization models you showed tend to follow a circular layout?”

I was not only intrigued by her question but also somewhat vexed that this plainly evident observation had never occurred to me. “That’s a great question,” I said, pausing, and followed with a candid reply: “I don’t exactly know why.” Later that same year, in September 2011, I became enthralled by the mention of an experiment that established a correlation between circular shapes and happy faces. From that point on, I became consumed by this topic.

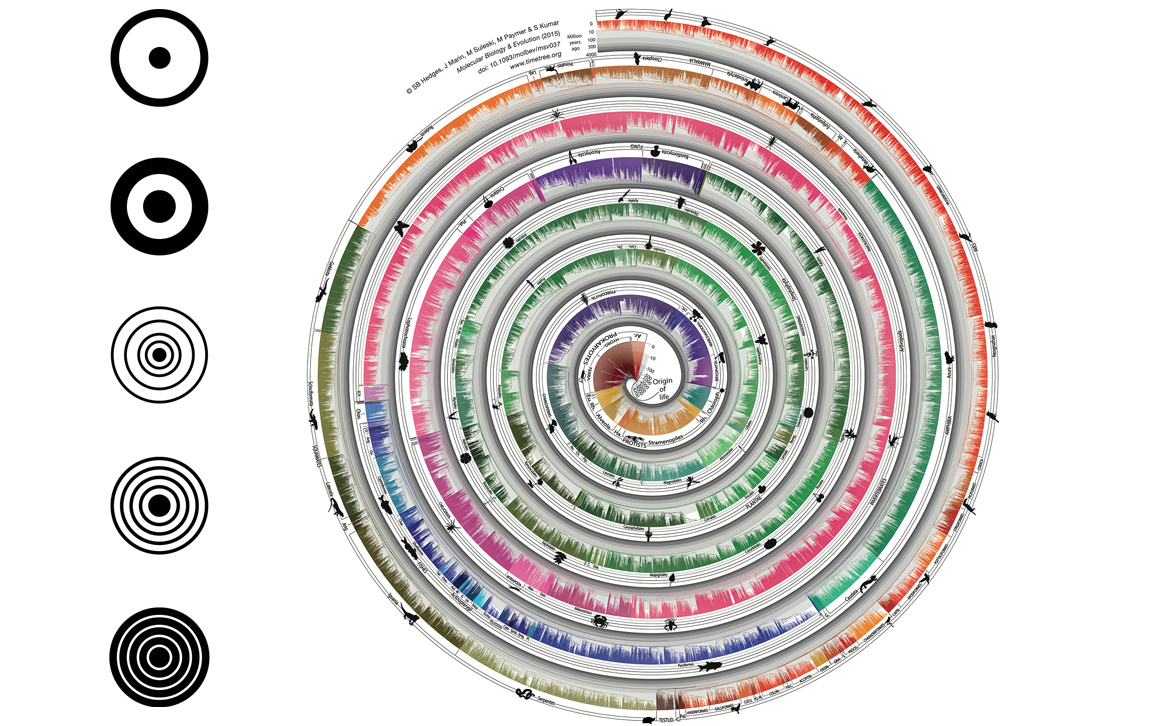

Image from S. Blair Hedges et al., 2015, Molecular Biology and Evolution 32:835–845.

As I delved into more visualization methods and approaches, the omnipresence of the circular layout became utterly overwhelming. Of all possible models and configurations—with endless possibilities for constructing diagrams and charts—why is the circular layout such an exceptionally popular choice for depicting information?

Man is a classifying animal. We understand phenomena by describing, grouping, and comparing them. This impulse is not just the basis of natural sciences; it’s also our primary method of comprehending history, architecture, literature, design, art, or any other cultural manifestation. One of the most universal and long-lasting visual metaphors is the circle. Notwithstanding our advanced modern tools and piles of new data, we are still using visual metaphors that are similar and at times identical to those used to convey knowledge throughout history.

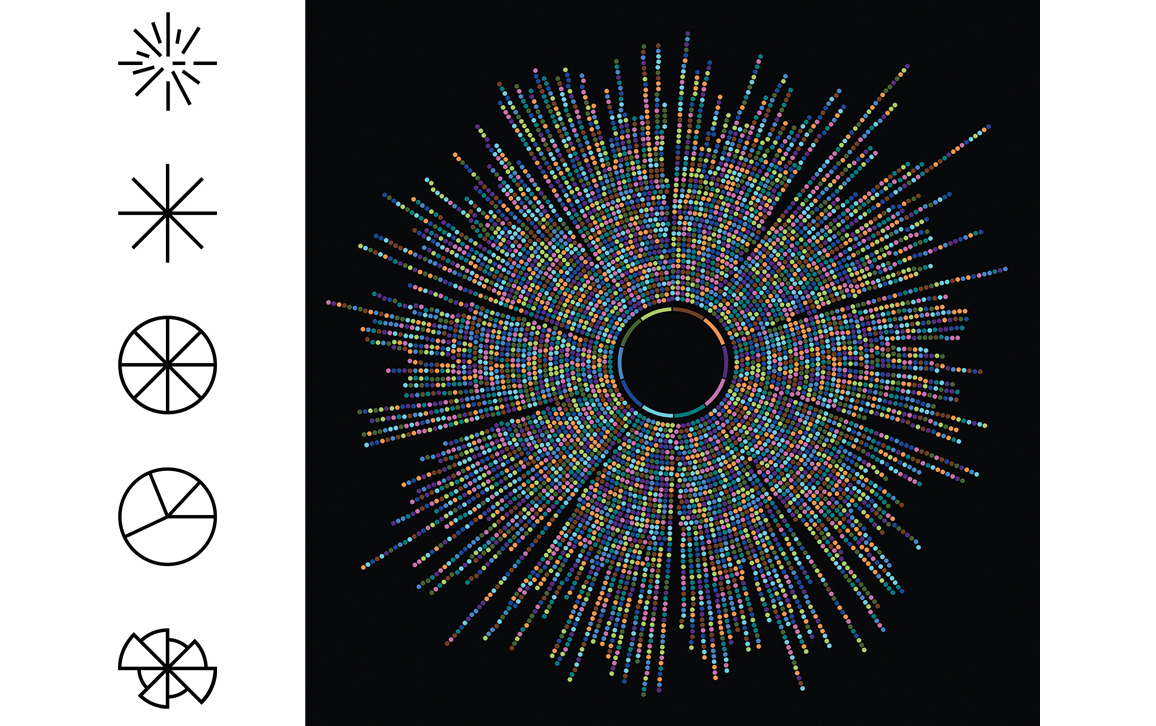

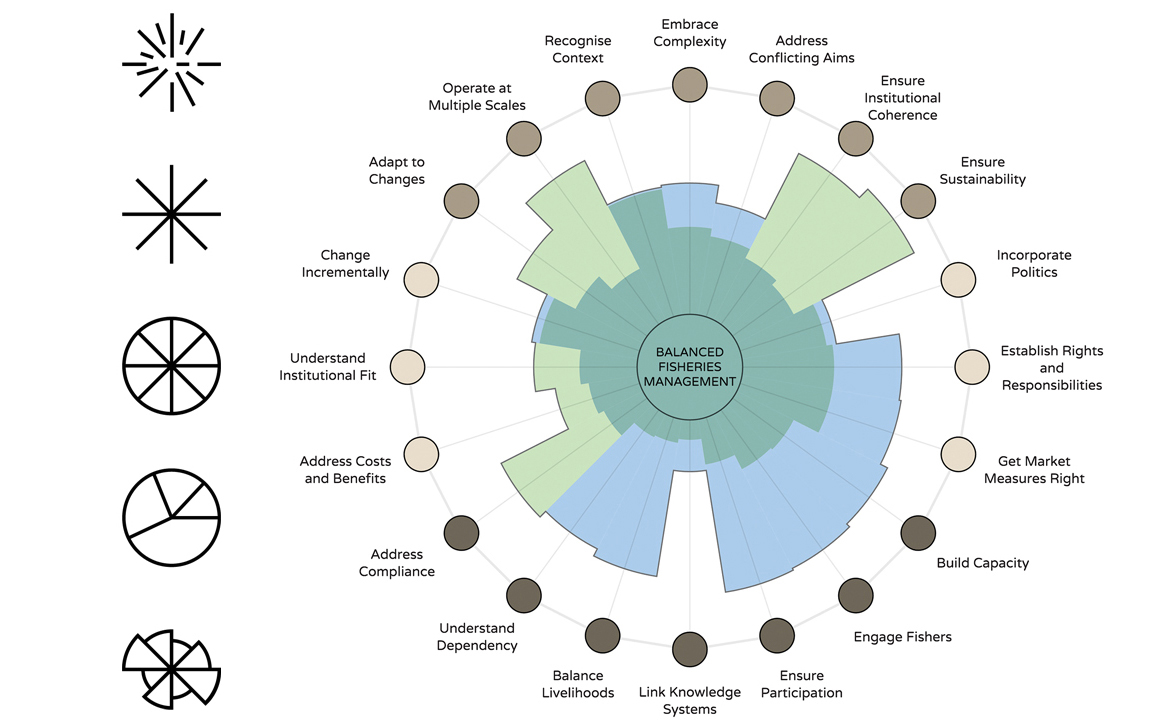

If we take a closer look at numerous diagrams and illustrations, we can perceive a concise set of variables underpinning most executions. These graphical variables steer the models presented here. It’s a small number; yet, when intelligently combined, these models create endless possibilities for depicting the most complex subjects. The patterns are grouped into seven archetype families, based on their visual configuration.

A preference for circular shapes is deeply ingrained in all of us from birth. At five months of age, before they utter a word or scribble a drawing, infants already show a clear visual preference for contoured lines over straight ones. In a seminal paper published in 2006 in Psychological Science, cognitive psychologists Moshe Bar and Maital Neta conducted an experiment in which 14 participants were shown 140 pairs of letters, patterns, and everyday objects, differing only in the curvature of their contour. The results were not completely surprising: Participants showed a strong preference for curved items in all categories, particularly when it came to real objects. To better understand this bias, the same pair of scientists conducted another study one year later, this time by mapping the cognitive response using functional magnetic resonance imaging. The results were quite conclusive. Sharp-cornered objects caused much greater amygdala activation than rounded objects. A well-studied region in the temporal lobe of the brain, the amygdala’s primary function is to process stimuli that induce fear, anxiety, and aggressiveness and to deal with the resulting emotional reactions. A 2013 study by researchers at the University of Toronto at Scarborough found that curvilinear spaces were perceived by participants as more beautiful than rectilinear ones, exclusively activating the anterior cingulate cortex—a brain area associated with cognitive functions involving empathy, reward anticipation, and the emotional salience of objects.

Most of the research in this area seems to point out an evident truth: We prefer shapes and objects that evoke safety, and we are not so fond of objects with sharp angles and pointed features, because they suggest threat and injury. As the ultimate curvilinear shape, the circle embodies all the attributes that attract us: It is a safe, gentle, pleasant, graceful, dreamy, and even beautiful shape that evokes calmness, peacefulness, and relaxation.In 1978 psychologist John N. Bassili found that happy faces resemble an expansive circle, whereas angry faces resemble a downward triangle. The dichotomy of circular, happy faces versus triangular, angry faces seems to be rooted in two primordial human imperatives: our need to read our fellow humans’ facial expressions and our need to detect threats as quickly as possible. Thus, our ability to infer emotions from minimal perceptual input helps explain why the elementary geometric shapes of the circle and the triangle can act as abstract representations of joy and anger.

The more we dig into our shared cognitive biases, the more we recognize that the copious layers of cultural meaning we have added to the circle through the ages are ultimately grounded in an instinctive evolutionary proclivity. As with many other areas of human aesthetics, the circle’s inescapable beauty seems deeply rooted in our biology.

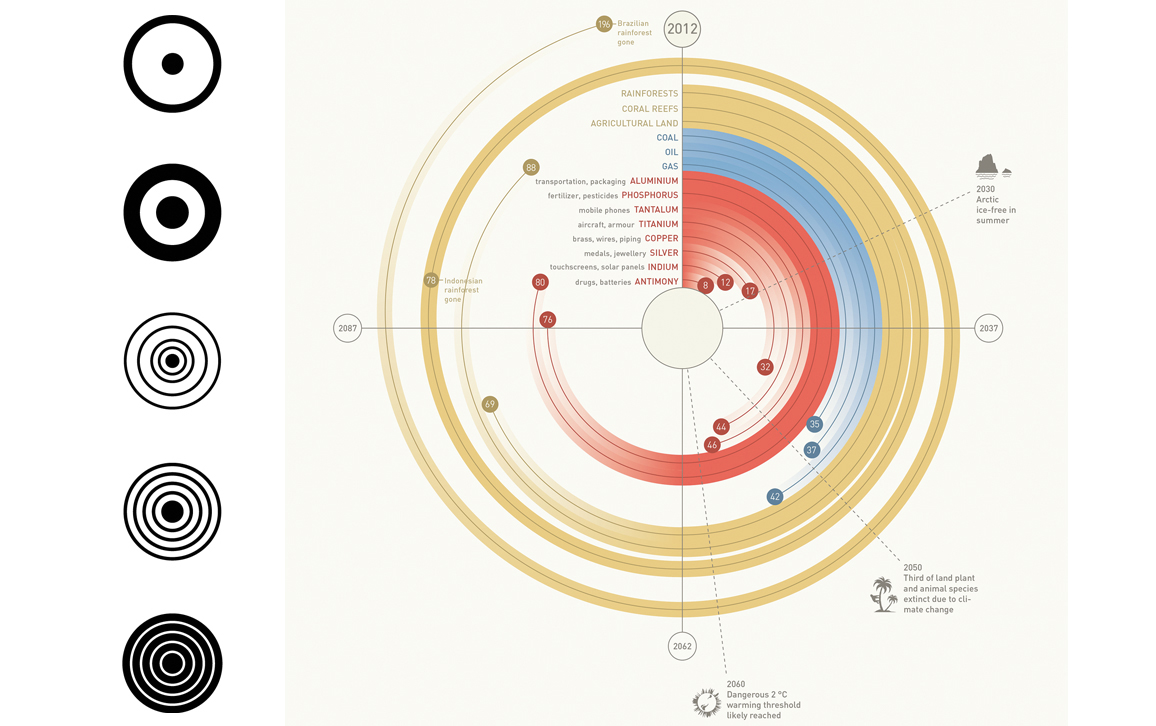

Image created by IIB Studio, 2011.

Image by Christian Ilies Vasile, 2012.

Image by Erik Jacobsen/Threestory Studio and Peter Cook, 2014.

Image by Christina Bianchi, Anna-Leena Vasamo, and Bryan Boyer, 2010.

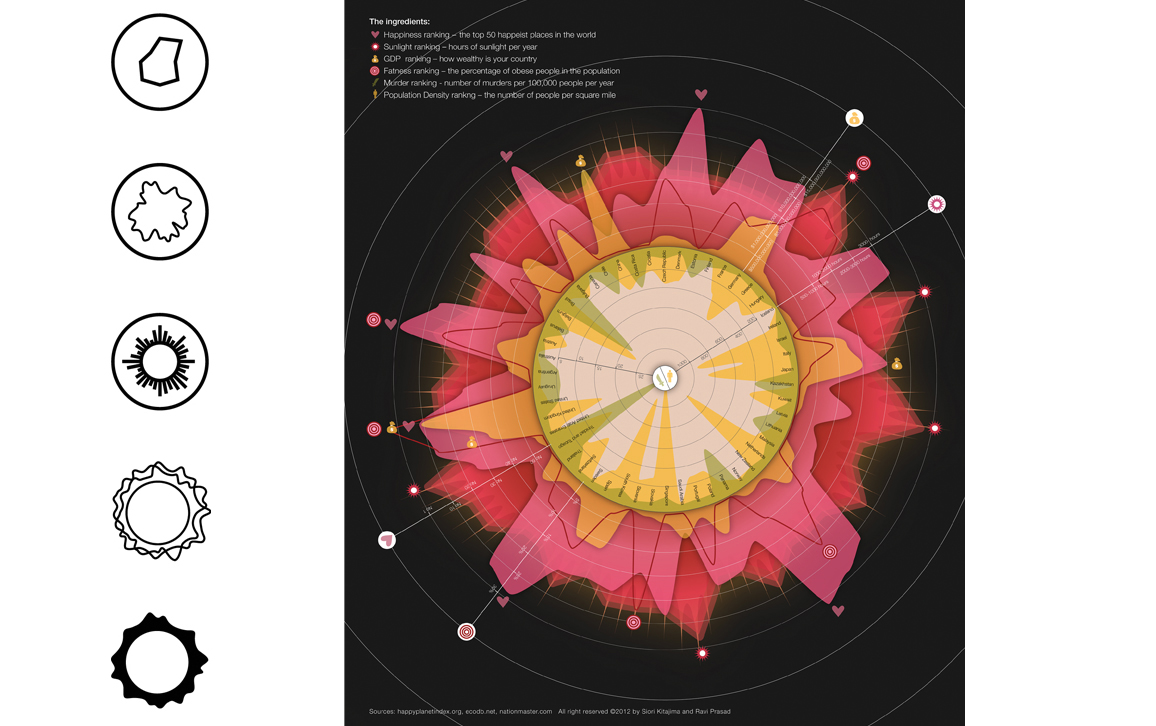

Image by Siori Kitajima and Ravi Prasad, 2012.

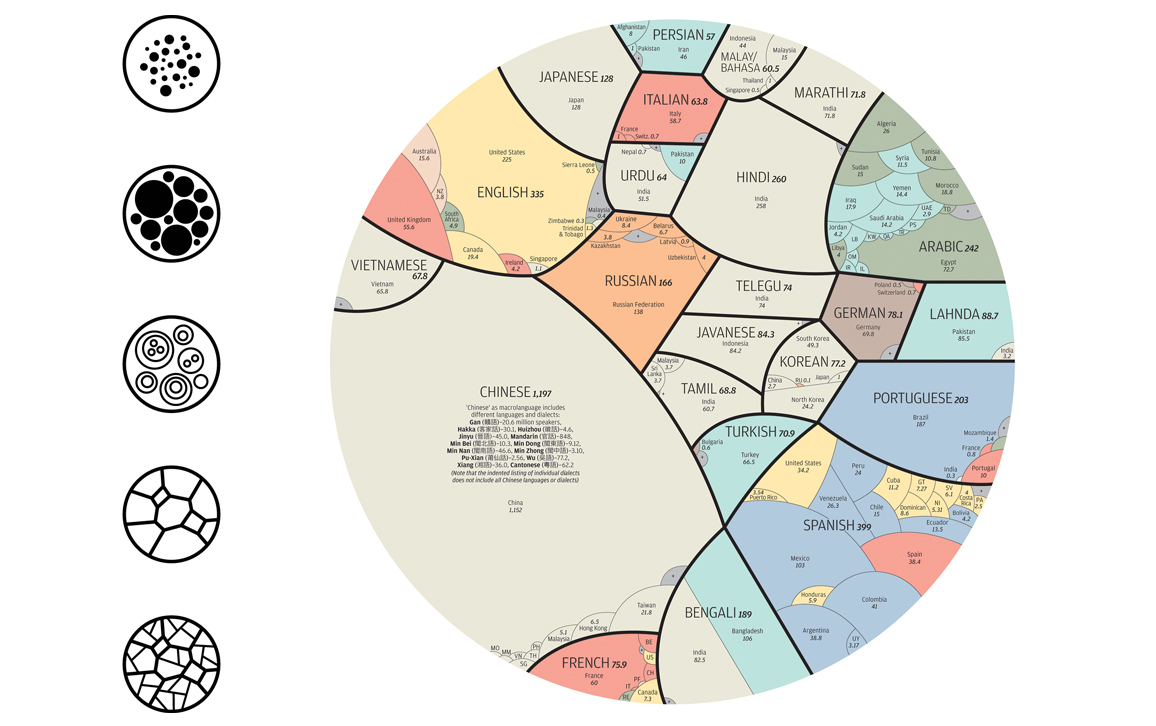

Image by Alberto Lucas Lopez, 2015.

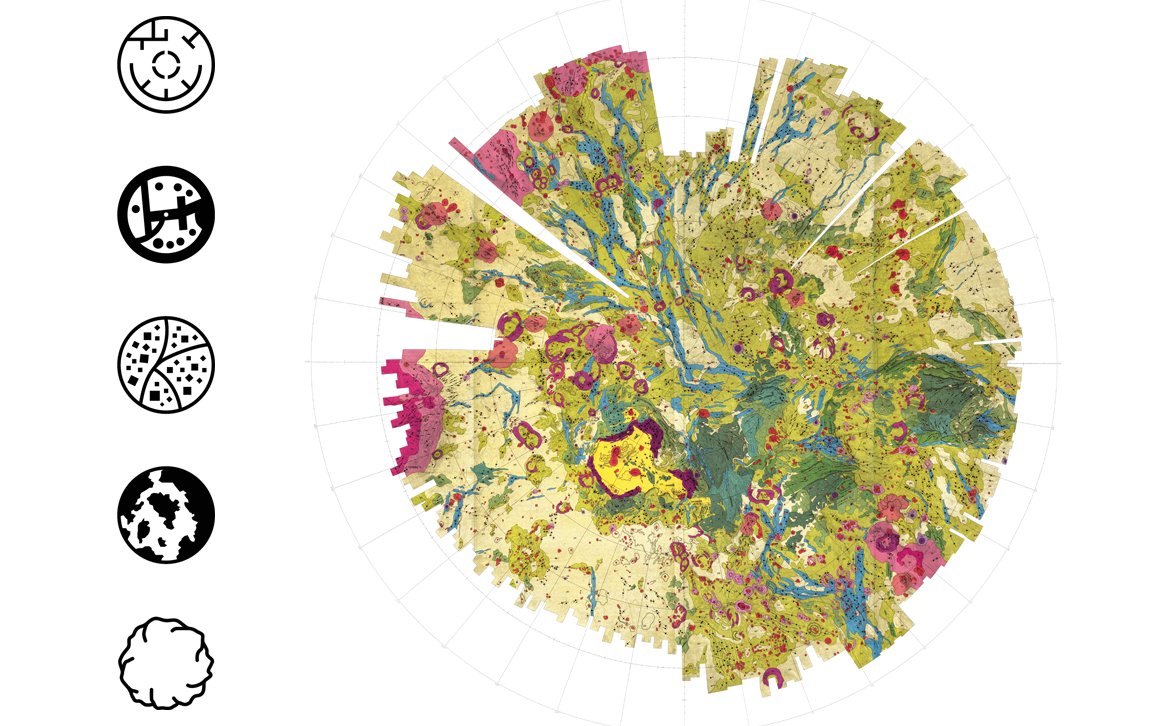

Image courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, 1989.

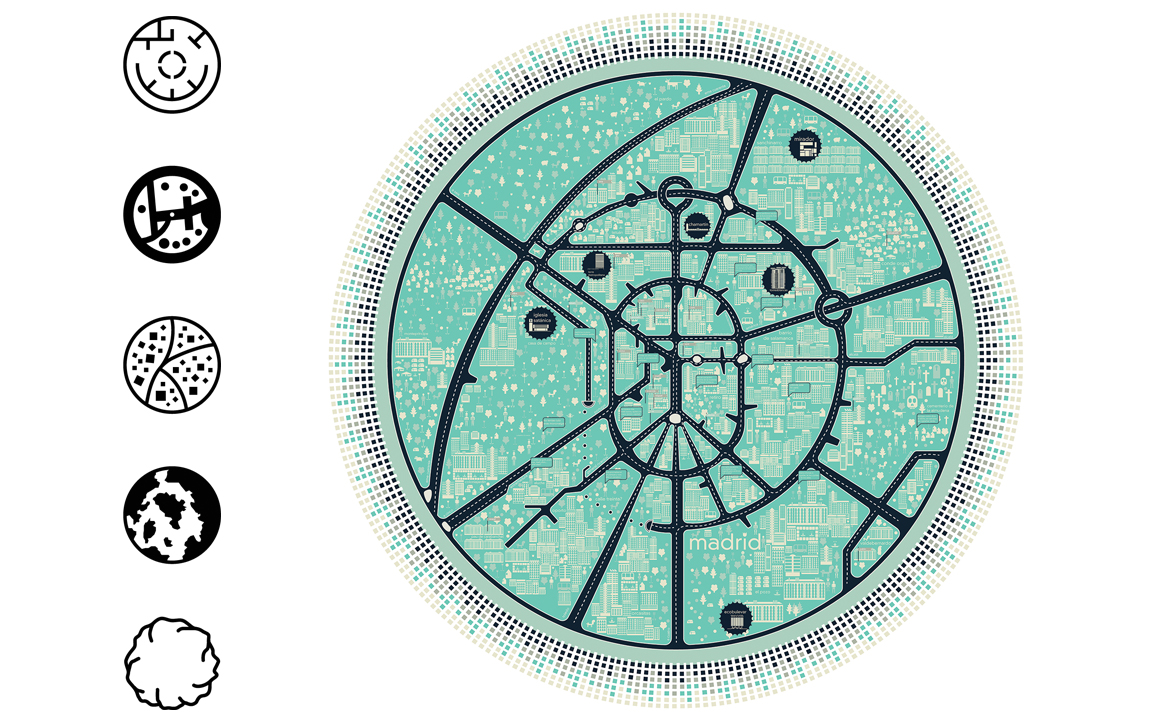

Image by Carlos Romo Melgar [C31913], Cosmographies, 2010.

Image by Josh Gowen [Signal Noise], 2013.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.