Ending the War on Drugs

By Amanda Latimore

The most influential factor in the exponential growth of a militarized, excessively penal, and discriminatory criminal justice system began with 1970s policies on substance use.

September 10, 2020

Macroscope Sociology Social Science

In 1968, as a response to the death of Martin Luther King Jr., an Iowa schoolteacher and civil rights activist Jane Elliott conducted a social science experiment, now infamously called the Brown Eyes Blue Eyes study, with her third-grade students. In this experiment, students with brown eyes were made to wear blue collars, segregated on the playground, and admonished by Elliott for being less intelligent, slower, and generally inferior members of the classroom, while blue-eyed students were held in high esteem and received preferential treatment. Over the course of a few days, Elliot was able to demonstrate how quickly children learned to discriminate against their brown-eyed peers based on a false sense of superiority. Equally illuminating: The students were jolted into a process of unlearning that superiority when Elliott reversed the blue-brown hierarchy, forcing the blue-eyed students to gain perspective on the experience of marginalization.

In today’s era of colorblindness, affirmative action, and Black elected officials, one might think such a harsh lesson on blatant discrimination is no longer necessary. The hard-fought battles of the Civil Rights Movement abolished overtly racist policies and established (at least a public-facing) intolerance for racism in the United States. However, the May 2020 murder of George Floyd served as a tipping point for a string of cases of white police brutality against Black citizens, opening the door for public discourse and research on discriminatory policing and persistent racial inequity.

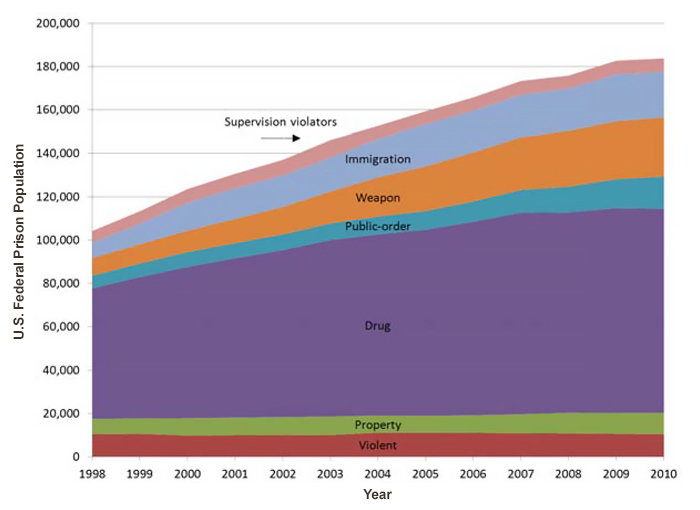

As jurisdictions across the nation are considering how to activate their communities to address social justice disparities, more attention must be given to the data that show what may have been the single most influential factor in the exponential growth of a militarized, excessively penal, and discriminatory criminal justice system: the War on Drugs.

Figure courtesy of the Urban Institute.

Header image courtesy of the Legacy Museum.

Land of the Free?

In 1971, three years after Elliott’s Brown Eyes Blue Eyes study, Richard Nixon declared a war against “public enemy number one.” The named enemy? Drug use. The financially bloated War on Drugs is a demonstrated failure at curbing the drug trade and the use of drugs. The only visible impact of this 50-year tragic waste of taxpayer dollars has been the exponential growth of the prison system, the demonization and stigmatization of people who use drugs, and the mass incarceration of people of color. There is no evidence that Black Americans are more likely to sell or use drugs; indeed, analyses have demonstrated they are significantly less likely to use and sell drugs. Nevertheless, they are more subject to over-policing and homicide at the hands of law enforcement, and have higher rates of arrest, booking, conviction, aggressive sentencing, and restrictions from reentering society for drug- and alcohol-related charges than white Americans.

The covertly sanctioned marginalization of people of color, brought to you by the publicly funded War on Drugs, could leave a critical mind questioning if drugs were ever really the “public enemy” at the outset. In plain sight, the United States had created its own new social science experiment.

Stop-and-frisk policies and racial profiling are more present in communities of color. A New York City report demonstrated that although Black and Latino residents were 54 percent of the population, they consisted of 84 percent of the stops. This disparity proved to be wholly unwarranted as, among those subjected to this policy, people of color were half as likely to be carrying a weapon and one-third as likely to be carrying contraband than white people. Yet the use of police force was greater for people of color.

Over-policing of Black communities leads to Black arrest rates 10 times the white arrest rate for possession of marijuana. Once arrested, people of color are more likely to be booked, convicted, and serve time for drug- and alcohol-related misdemeanors than white people. Given the same charges, white people are given more leniency in judges’ sentencing decisions. Mandatory minimums and three-strikes-you’re-out laws further exacerbate the racial disparities in sentencing. Insufficient legal representation among the poor result in innocent people accepting pleas of probation for drug crimes they didn’t commit. Although many don’t realize that probation launches them into a lifetime of marginalization because they have a criminal record that limits their employment opportunities, it seems a small price to pay to avoid the risk of sentences so severe that Human Rights Watch released a report imploring the United States to reform its sentencing practices.

Given that the racial discrimination at every encounter with the criminal justice system is fortified by the next encounter, it is no surprise that Black and Latino people are one third of the U.S. population but make up 59 percent and 77 percent of the state prison and federal population, respectively, for drug offenses.

Throwing Away the Key

At the end of the Brown Eyes Blue Eyes study, Elliott reflected with her students on how it felt to be discriminated against. As the third graders emphatically ripped and threw away their blue collars, one youth explained, “It’s like you’re chained in a prison and you’re throwing away the key.”

Victims of the War on Drugs are serving decades-long, and in some cases life, sentences for low-level, first-time drug offenses, even as these same drugs have become legal in other parts of the United States. After paying one’s “debt” to society, individuals incarcerated for drug-related convictions are released into societal conditions that present multisystemic barriers to employment, transportation, and civic participation. Some of these legalized exclusions purposefully target people with drug-related federal or state records, barring them from the receipt of public benefits for housing and food. Incarcerated individuals are also released with financial debts to the legal system such as fees for “room and board” while incarcerated and for covering the cost of their own community supervision. Discrimination against people of color while pursuing employment is amplified for people of color with criminal records. Research suggests that employers may be more willing to hire someone with minimal work experience over someone with a criminal record with the appropriate work experience.

Many face difficulties paying the fees, which initiates a cascade of events, including the suspension of one’s driver’s license, late fees, arrests, and longer probation and parole. The feedback loop continues as extended engagement with the criminal justice system, which further complicates issues with employment, housing, food, transportation, and the ability to care for one’s family. For those not serving life sentences, the War on Drugs ensures that people incarcerated for drugs continue to pay long after the completion of their sentence.

The racialization of drug policy has become even clearer today as one compares the rhetoric and policy actions taken during the crack epidemic of the 1980s and 1990s (for example, mandatory prison sentences for first-time offenses) to those taken during the opioid overdoses of mostly white drug users that took Americans by surprise in the 2000s and 2010s (for example, making predatory pharmaceutical companies pay). Stigmatizing views persist across color lines in the medical community, media, and the general public that addiction is a moral failing despite ample evidence that it is a medical condition that can be effectively treated, which only adds to our country’s discriminatory environment.

Not Just “a Few Bad Apples”

Research that recognizes the social determinants of health shows that police brutality is merely a symptom of a much deeper problem with the carceral system. Those fighting for social justice must expand the scope of action beyond the idea that police brutality is about a “few bad apples” and ineffective police departments. Reducing police violence must also involve reducing the disproportionate exposure of marginalized populations to police, including the changing of laws that are seemingly colorblind but are inequitably enforced. Drug laws, if taken at face value, are not written to corral people of color into jail cells. However, drug laws are enforced in ways that lead to their mass incarceration and contribute very little to improving–and in many ways increase harm to–public safety and health.

Today’s social justice movement is a marquee opportunity to pay attention to the overwhelming evidence that drug policy reform is needed and to go beyond just a public-facing intolerance for racism. The unprecedented presence of racism in the national dialogue is making it possible to overturn deeply rooted racialized policies. The evidence is overwhelming that ending the war on drugs is an essential component of the social justice movement. After decades of police brutality where justice was neither swift nor decisive, let’s not continue to be bound by inaction. This country has an opportunity to create a new social science experiment in which the War on Drugs becomes a War on Discrimination.

The views and opinions expressed in this post are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of American Scientist or its publisher, Sigma Xi.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.