Family-Friendly Science Communication

By Stacey Lutkoski

All-ages programming is challenging, but Tinkercast's Wow in the World is popular among both parents and children.

April 1, 2020

Science Culture Communications

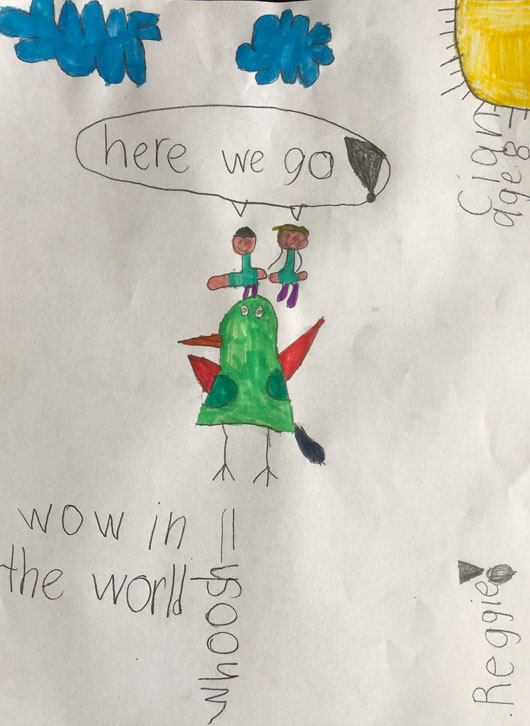

If your kids have been nattering on about a pigeon named Reggie or someone called Grandma G-Force, they haven’t gone “bonkerballs”—they’ve just been listening to NPR’s first podcast for kids, Wow in the World. The weekly show, which premiered in May 2017, stars Mindy Thomas and Guy Raz as friends who live in a world much like ours, but with a little sprinkle of magic (for example, Thomas’s character lives in a gingerbread house—or, rather, a gingerbread mansion, a detail she makes a point of clarifying at every opportunity). Each episode, Thomas and Raz examine a story from science news with a cast of crazy characters, such as the aforementioned Reggie, whom they ride like an airplane to their various adventures.

Tinkercast

Thomas and Raz are both veteran broadcasters: Thomas is the long-time host of Absolutely Mindy on Sirius XM’s Kids Place Live channel, and Raz is an award-winning journalist and the host and cocreator of NPR’s How I Built This. They teamed up with children’s programming pro Meredith Halpern-Ranzer to create a podcast company, Tinkercast. Their combined expertise helps Wow in the World hit that elusive sweet spot where it is truly fun and educational for all ages. The jokes play at several levels. For example, in a recent episode about the star Betelgeuse, Thomas dons a “How I Built a Bear” suit; my six-year-old giggled at the image of a woman wearing a giant teddy bear as a coat, while I chuckled at the play on names (How I Built This plus Build-a-Bear Workshop). Even my three-year-old, who is still too little to get some of the jokes, loves the show and laughs hysterically at the many Mindy-isms, such as her liberal use of the word “bonkerballs.”

When I talked to Thomas and Halpern-Ranzer in late February, COVID-19 was on our minds, but we didn’t know that soon much of the United States and the world would be working from home and sheltering in place. Many parents—including me—are setting up home schools alongside their home offices. Wow in the World was already go-to content for my family’s road trips because it is something everyone in the car can happily agree on. In the spring of 2020, though, the podcast has renewed importance as a way to relax and listen to a funny story while still learning about the latest science news.

Tinkercast

In response to the sudden need for more entertaining and educational content, Tinkercast has launched a spin-off podcast, Two Whats and a Wow, which an announcer describes as “everyone’s second-favorite game show after ‘Fishing for Compliments.’” This seven-minute game show is a take on the party game “Two Truths and a Lie.” Thomas and Raz list three science tidbits about that day’s theme, such as giraffes. Listeners guess which of those tidbits is a science fact, and which two are science fiction. The next day, Thomas and Raz return to fill kids in on the answer, present a new quiz, and give a scientific challenge related to that day’s theme (such as creating a giraffe neck out of items found around the house).

I spoke with Thomas and Halper-Ranzer about how they developed Wow in the World and how they see themselves in the larger #scicomm space.

Transcript

Stacey Lutkoski

So much of what you hear about science communication is aimed at adults or older children who have already had years of taking classes in science.

[music begins]

But what about younger kids? Or even science communication for whole families?

Mindy Thomas

So scientists are so much like kids! And it makes me crazy when kids say, “I don’t really like science” and I’m thinking, “I didn’t like science either as a kid”—it’s all in how—it’s like vegetables—it’s all in how it is prepared or presented to you.

Stacey Lutkoski

On this episode of the American Scientist podcast, an interview with Mindy Thomas, co-host of WOW in the World podcast, and Meredith Halpern-Ranzer, chief executive of Tinkercast, which produces the show. I’m Stacey Lutkoski.

[music ends]

It’s the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, and like many parents, my children are at home, and I too am working from home. Our family was already listening to Wow in the World--a kid-friendly science podcast that began in 2015. Last month, March, 2020, the same team started a daily game show, Two Whats?! and a Wow! which the distributors of the show, National Public Radio, say was created “as a rapid response to worldwide school closures affecting almost a billion children due to the coronavirus.”

[Clip starting 2:00]

Thank you for joining us on our brand-new game show: Two Whats?! and a Wow!

I spoke with Mindy Thomas, co-host of the show, and Meredith Halpern-Ranzer, the chief executive of Tinkercast, which produces the show. Here’s our interview.

Stacey Lutkoski

My kids are so excited I get to talk to you

Mindy Thomas

Aww, that’s so nice. Say ‘hi’!

Stacey Lutkoski

Could you tell me a little bit about how the podcast came about? How you found each other? Mindy?

Mindy Thomas

Yeah, so Guy and I actually met through Twitter

Stacey Lutkoski

Guy Roz, the co-host of the show.

Mindy Thomas

He was listening—this was probably six years ago—he had been listening to my other show. I have a morning show for kids and family on Sirius XM Kids Place Live. It's called the Absolutely Mindy! show. And he had been listening in the car on the way to school with his kids. And then he tweeted—and I will remember the tweet forever now—“Absolutely Mindy! is the Morning Edition of kids radio.” And I was so thrilled to get that tweet. I was a huge fan of Guy and the TED Radio Hour. After that I sent him a message and I was like, “mutual admiration society.” You know, this is great! And I think I had invited him to one of our live events for Kids Place Live. And then we started talking and he asked me if I'd ever consider doing a kid's news segment on my show because he's a journalist. And I said, “Yeah, are you are you volunteering?” And he's said “I would love to do it.” So he we started a kids news segment called the Breakfast Blast Newscast. And it aired every Friday. It was a short segment, maybe eight minutes long. And we quickly realized that when it came to news, the news that was full -- first of all, it was just a reminder that how complicated the world is and how bleak the news can be for kids. And there's a fine balance between what you, you know, wanting kids to feel informed and wanting kids to feel agency in their world, but also not to totally bum them out with stuff that they don't have the response—they shouldn't have the responsibility of worrying about yet. So we quickly realized that some of the most amazing stories of hope and progress were in science. So it sort of morphed into more of a science segment than anything, and it got great response from our listeners. You know, Guy was the journalist, I was the radio show host, and he would bring me the news. And then I acted as a proxy for the kids asking questions that the kids would want to know. And, you know, making it silly. We added some sound effects, we produced this thing. And Guy, I think, was the first to realize like, “We're onto something here we should—Let's make this bigger. Let's make it this its own thing. Let's do a podcast.” And I was really reluctant to do that because I had this great full time job at Sirius XM. But after enough nudging, he got me to take this leap of faith. We started our company, Tinkercast, and Wow in the World was our first show from Tinkercast, and we brought Meredith on to help us launch it and quickly made her our CEO. And that was sort of how it all began. So the Breakfast Blast News Cast was like a baby version of what Wow in the World has become. And in a lot of ways, I would say, Wow in the World when we started wasn't even what it is now. So much of it has grown into what it is very organically. I don't even think that we meant for it to be the narrative that it is or to create this world around us as characters and, you know, these other characters on the show, we did not ever plan them out. They just showed up in the writing. So, the whole thing has happened very organically, and we're so proud of it, and we love making it. It's been so fun. I feel like I'm learning something new every day along with our listeners.

Stacey Lutkoski

Meredith, I listened to your interview on Kidtech and you mentioned that you were initially a little bit reluctant to sign on as CEO. But after you heard the first episode, you became really enthusiastic and you jumped right in. So I was wondering, what was it about that first episode that made you want to make that commitment?

Meredith Halpern-Ranzer

Well, I, you know, my background is in children's television. So for 20 years and working in a network and yet I was coming home to a child—my son—who wasn't really watching a lot of TV and nor did I really want him to watch a lot of TV. So I loved the idea of audio. I grew up listening to like records and, you know, like, audio stories. And by the time that guy Mindy we're planning— starting to plan things—I had gotten really into podcasts myself, like as a grown up listener. But I just wasn't sure. I was reluctant, like, were kids really going to choose to listen to audio as opposed to watching something on a screen? I just wasn't sure of that because my whole training everything I knew was about how to make engaging content on the screen for kids. But yeah, so when I heard it, the first episode, I listened with my son, and we just are sitting on the couch and like kind of looking at each other with like this face of “Wow, I didn't know that.” But like, so, I saw the images coming to life in his brain and they were coming to life in my brain. Amazing. And also a leap of faith as Mindy said.

Mindy Thomas

And I like that families...

Stacey Lutkoski

Mindy?

Mindy Thomas

...you know, we try to make this show as engaging for adults as it is for kids. And I know that every one is going to learn something because it's all based on new scientific research. So I love the idea that parents and kids listen together. And that after they listen to an episode, they have things to talk about. And if you don't have things to talk about, we have conversation-starters that you can click on and bring them up in your car or wherever you are. So I love, you know, creating any kind of content that brings parents and kids together on the same playing field.

Stacey Lutkoski

How do you hit that space that appeals to all ages? That seems like such a narrow line to hit.

Mindy Thomas

Well, I feel like, you know, like I said, the science itself is all new. So we try to teach sometimes--and I use the word “teach” pretty broadly--but we try to, I guess, show broader scientific concepts through new research and new discovery. So like I said, the parents will be learning something new, because we've searched deeply for some of these stories. They're not always science stories that everybody hears about. So everyone's going to learn something. I feel like the jokes are a lot of times told on two levels where parents might laugh at the joke, kids might laugh at the situation. So the jokes are on both levels. And I feel like a little bit of silliness is just sort of universal.

Stacey Lutkoski

How are you finding your stories? We get a lot of press releases and things like that. Is that the route you're going or...?

Mindy Thomas

Yeah, we get press release. We—"everywhere" is the answer. I mean, I am searching everything from the New York Times science section to, you know, I get EurekAlert, Science News Daily pops up. Any—I—look, we're constantly scouring every science news site we can find looking for interesting things to write about.... If we can make a narrative around a story, we know that we can make this relate to a kid’s world somehow.... And I think kids would be more interested in science if they realize that scientists are not afraid to ask ridiculous questions. They're not afraid of being wrong because a lot of times when you're doing a scientific experiment, things don't turn out the way you're supposed to—their—you think they are. I mean, that's the whole premise of a hypothesis like this, what you think was going to happen—Is that going to happen? And a lot of times it doesn't, or you discover something new that way.... And that’s the other thing, so scientists are so much like kids! And it makes me crazy when kids say, “I don’t really like science” and I’m thinking, “I didn’t like science either as a kid"—it’s like vegetables—it’s all in how it is prepared or presented to you.

Stacey Lutkoski

Kids can be very sensitive about being talked down to, and I never get the sense from your show that you're talking down to them. How do you—at what level do you decide to explain things? And how do you kind of get it in there without that condescension?

Mindy Thomas

I think when we write this show, we're not thinking like, “How are we talking to kids?” I feel like some of these things are so complicated to begin with, but I feel like we're breaking them down for anybody. We're breaking them down for ourselves in a lot of cases. There's a lot of times I'll read one of these studies and I have a ton of questions after and I have to contact the scientists who wrote it. And I ask, you know, like...

Stacey Lutkoski

That was one of my questions was whether you consulted a scientist.

Mindy Thomas

Yeah, you can respond in the most basic—like talk to me like I'm a six-year-old. And I think there's no shame in that. These journals are written like a foreign language sometimes, and even a lot of science articles that we find they feel like they're being written for other scientists or other science communicators. And I think for just regular people, they have to be broken down quite a bit for us all to understand and relate. Also I mean, we're both parents, I've been talking to kids live on the radio every day for 19 years. So I don't think it's something that we really think about, like “How do we not talk down to kids.” That's just what we do. I feel like I could, I mean, other than how silly it is, I feel like I could almost make the same—I’d break it down the same way if I was making a show for adults.

Stacey Lutkoski

I read that you and Guy Roz take turns writing the episodes but they seem to have a very consistent feel to them. What’s that process like?

Mindy Thomas

Yeah, so it's Guy and I and we have a third writer Thomas van Kalken. And I don't know, I feel like we've just—we spent a lot of time in each other's heads. And I spent a lot of time with Guy in my ears. I don't know how other than just.... I'm the head writer of the show. So I'll go through everybody's scripts and, you know, change words here and there rephrase things, thinking like that “Well, we wouldn't—he wouldn't really say this, or I wouldn't really say this.” But, you know, I would rephrase it in different way. I don't know I feel like it just has a style or an aesthetic that we all like—it's ingrained in all of us at this point.

Stacey Lutkoski

And I read also that it took a little bit of trial and error to get the right voice because at first it came across as a little like Guy explaining science, even like a little “mansplainly.” So how did you find that?

Mindy Thomas

That was not a hard thing to find. I mean, I am a firm believer that I think when it comes to girls, there's a lot of people that will tell you or send you signals that this is the right kind of girl to be. And I you know, girls are strong and fierce and smart and they are but they can also be silly or whatever. So I—and I feel like myself as a woman, I am silly and I'm smart. And I'm proud of that. I don't take things too seriously. And I don't think I have to take things too seriously to be treated seriously. So, when we started the show, the dynamic at first was a little bit more like how it was when Guy was doing this Breakfast Blast Newscast on my other show where I was the host and he was coming on as the journalist. You know, for some reason, we thought that was going to translate to this as well. And it didn't because it was a whole new audience. So we realized quickly, like, “Oh, wait, this doesn't work out. You're not the journalist anymore. I'm not the host. Like we've got to balance this out.” And I was so glad that we did and I know. So I love the Mindy character now. I feel like she is very smart. She's very curious. She's also really silly, but she also, you know, she's not afraid to... she kind of throws caution to the wind and will try anything and do anything. And I feel like Guy’s character is a little bit more—he's a little bit more cautious, which and I feel like there's room for both. I feel like these two characters, there's a little bit of both in every person and there should be and we have to balance those out in ourselves. So yeah, we were both really happy to, you know, it was like hard feedback at first like “Wait, what?” Because it was hard not to take it personally at first, like, “What do you mean?” Like Guy’s like, “I'm not a mansplainer.” And I was like, “I'm not a ditz.” And then we realized these people don't know us. This is not about us. Oh, like we got it. We have to balance this out. So it was a pretty easy transition to make just to make sure that the whoever's the keeper of the knowledge in each episode is balanced. And then for both of us—both of us will ask questions both of us will know things.

Stacey Lutkoski

Meredith, I read that you were thinking about different ways to expand—I think the term you use was “extensions.” What kind of ideas do you have in mind?

Meredith Halpern-Ranzer

Well, so we have a bunch of extensions. So our goal has been to try to get it out—get this brand of Wow and all of the great things that we're doing—out into as many communities and locations as possible. So we have, you know, our live shows that we perform once a month in a different city. We have a book deal—a book coming out in 2021 with Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Last year we got a grant from National Science Foundation to make an in-school program using Wow in the World content. So we’ve been working on that. So yeah, we have a lot of different ways that we try to like get out beyond just, you know, the podcast platform.

Stacey Lutkoski

Could you tell me more about what that in-school project would look like?

Meredith Halpern-Ranzer

Yeah. So we built a prototype last year under this grant and tested it. And basically what our hope is with it is that, you know, our show is a show about science as well as curiosity, and it's a show that gives kids agency in their world and helps to bring news to them. We did a lot of research and talking with a lot of teachers and really came to understand that the area that they feel the least comfortable teaching and have the least confidence teaching is science.

Stacey Lutkoski

Oh, wow.

Meredith Halpern-Ranzer

And so, you know, there's new standards -- next generation science standards -- that are being rolled out in many states. And so with these new standards, the intention is to get kids to do more hands-on science and to extend into STEM and STEAM more with science. And that's all well and good. But the teachers need to feel comfortable doing that. So our hope with what we're building is that around our show -- our show would be sort of like the engagement piece for kids and students -- and around the show we would bake in activities that really take them through the scientific practices of questions and hypothesis and predictions and observation, and then ultimately lead to hands-on experiments as well as, you know, creative innovation.

Stacey Lutkoski

Would it be app-based, or...?

Meredith Halpern-Ranzer

It would be web-based, not app-based, actually. So we have already -- we do have a number of teachers that are members in our membership program. So we've donated over two-thousand memberships to Title One school teachers. And so we have this membership site. On the membership site we have all of our free podcasts as well as supplemental science content and creative content that goes around that episode. So we have crafts and recipes and book lists and experiments and worksheets and things like that. So you can listen to an episode, and then do this experiment in your class. Or you could, you know, read these books from this book list that's curated from a librarian. If you go to Tinkercast.com, you can sign up to become a member and then that's all -- it's a searchable database. So you can search by craft, you could search by experiment, or you can search by topic. You can search by scientific area, like Earth science and you know, life science and that. So that we already have. Our hope with what we're hoping to build is to create more of a web-based platform that teachers would be able to see where their kids are in terms of connecting to the science standards, and have a little bit more assessment built in.

Stacey Lutkoski

Do you guys see yourselves as part of the science-communication world?

Meredith Halpern-Ranzer

Yeah, we do. I think we—I think just like the character sort of became organic to our show, I think that became organic to the show, too. I mean, not really like obviously Mindy and Guy knew their intention was to make science news—bring science news to kids and create a really amazing, funny narrative around that. But I didn't know, maybe you did, Mindy, that science communication was such a big area.

Mindy Thomas

I didn’t!

Meredith Halpern-Ranzer

And we started getting tagged on Twitter with hashtag, you know, scicomm, and that opened our eyes to this whole world and we love it and would love to be more a part of that world.

Mindy Thomas

That's one of the other things that I might take away from this is like -- wait a minute—like being interested in science, for a kid listening, There's lots of different ways to have your hand in science. You don't have to be a scientist necessarily. Communicating science is also something that the world needs more of.

Stacey Lutkoski

Thank you guys both so much!

Meredith Halpern-Ranzer

Awesome—thank you!

Mindy Thomas

Nice to talk with you! Thanks for listening with your family and for talking with us for this.

[music]

Stacey Lutkoski

That was Mindy Thomas, co-host of WOW in the World podcast, and Meredith Halpern-Ranzer, chief executive of Tinkercast, which produces the show. For links and more about science communication, visit our website, American Scientist, and search for the keywords science communication. Yes, those are the words—science communication—it’s that important to us.

You’ve been listening to a podcast from American Scientist magazine, published by Sigma Xi, the Scientific Research Honor Society. This podcast was produced by Robert Frederick. I’m Stacey Lutkoski. Thanks for joining us!

[music ends]

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.