An Ethics of Land Relations in Science

By Katie L. Burke

Max Liboiron's inaugural book is a primer on untangling and resisting the Gordian knot of justifications, manipulations, and traditions that enable colonialism in science.

August 19, 2021

Science Culture Environment Ethics Ecology Geography Review Scientists Nightstand Social Science

Pollution Is Colonialism. Max Liboiron. 197 pp. Duke University Press, 2021. Paperback, $24.95.

As Max Liboiron points out in Pollution Is Colonialism,

Western science has long been identified as a practice that assumes mastery over Nature, reproduces doctrine over discovery, revels in exploration and appropriation of Indigenous Land, and is invested in a rigorous self-portraiture in which valid scientific knowledge is created only by proper European subjects. It’s also pretty sexist.

Scientists who strive for justice and equity in their institutions face an uncomfortable quandary: The knowledge systems that form the foundation of scientific research are entrenched in colonialist practices. This book is for them. It maps the path the author has followed in attempting to avoid scholarly and scientific practices that reproduce colonialism while conducting research on plastic pollution. Liboiron acknowledges that anyone taking on a similar goal will face difficult, paradoxical dilemmas, and that a solution that works in one context may not work in another.

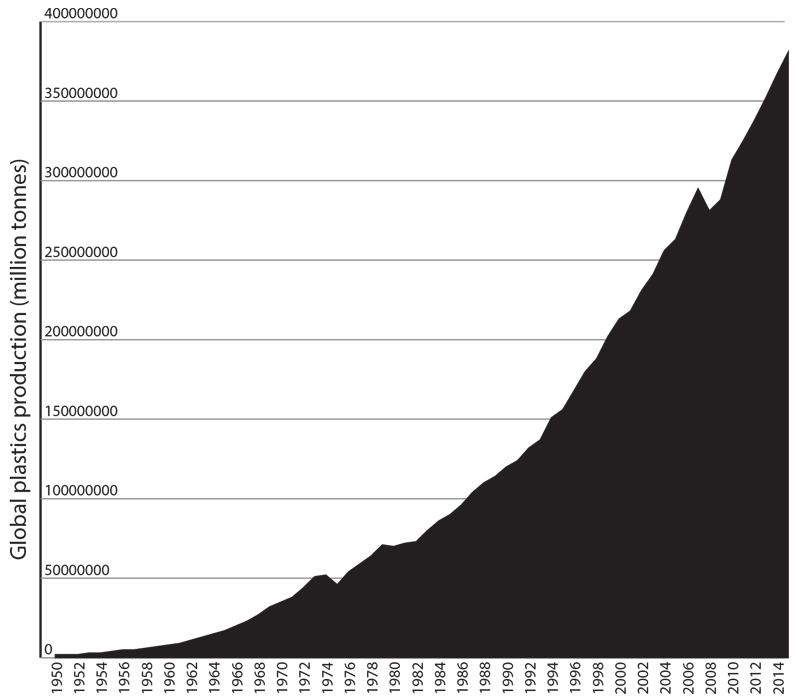

From Pollution Is Colonialism.

The context shaping the decisions that Liboiron makes is as follows: They are a Métis geographer at Memorial University of Newfoundland studying food sovereignty and plastics in the local marine food web while foregrounding the Indigenous concept of accountability to relationships. Liboiron focuses on not reproducing two particular features of relationships between settler colonialists and Indigenous people: genocide and assumed settler access to Indigenous Land. (Land with a capital L refers not just to physical land but also to the Indigenous concept of all the environmental, ethical, and spiritual relationships encompassed therein.) The central tenet of Liboiron’s work is conscientiousness—about Land relations for Indigenous people, and about land relations for everyone else.

Pollution Is Colonialism is a short, cerebral book that pulls together scholarship that spans science and technology studies, Indigenous studies, discard studies (research regarding waste and wasting), and knowledge systems outside of academia. The text requires the reader to pay close attention to definitions while exploring deep, paradoxical questions of ethics and epistemology, as the author painstakingly lays out a framework for doing science in a way that does not perpetuate colonial violence. Although the book focuses on plastic pollution, it is relevant to all areas of science, because it illustrates the ways that colonialism can show up in the sciences.

Photo by Max Liboiron. From Pollution Is Colonialism.

One of the book’s main points is that colonialism may be perpetuated even by researchers who have the best of intentions. Liboiron uses well-meaning sanitation engineers Earle B. Phelps and H. W. Streeter as an extended example, referring repeatedly to their work and its influence. In 1925 the two men came up with what has since become the dominant understanding of modern environmental pollution. They created a model of the conditions under which water can purify itself and then set threshold amounts for potentially harmful substances—the threshold being the point at which water can no longer purify itself of the substance. They maintained that when substances were not present at levels that exceeded the threshold amount, they should not be considered pollutants at all. This approach created a policy loophole that allowed industries to deposit their waste in the environment without express permission.

“Phelps was a bold environmental conservationist,” Liboiron writes.

Unlike his contemporaries, he believed polluted rivers could and should be saved from, rather than abandoned to, industrial pollution by using science to keep the pollution below a [certain] threshold . . . . But his theory . . . also assumed access to Indigenous Land. Phelps not only accessed Indigenous Land along the Ohio River to do his science; he also routinized state access by advocating for all rivers on all lands to be governed—carefully! precisely!—as proper sinks for pollution.

Another example of good intentions reinforcing colonial violence can be found in recycling projects that assume access to Indigenous Land for recycling centers and their waste. Actions based on this sort of assumption can have unexpected results that may make it harder in the long run to disrupt runaway increases in pollution.

Liboiron is not just writing about the practice of science; the book itself demonstrates how to practice anticolonial scholarship through the citations, introduction, acknowledgments, spelling, and formatting. Particularly intriguing are the footnotes—and that’s a sentence I never thought I would find myself writing! Liboiron uses footnotes to demonstrate that the knowledge the book imparts has many sources and to thank scholars directly for specific contributions; the footnotes also explain what particular scholarly choices have to do with colonialism. Liboiron often adopts a more conversational tone in the footnotes, displaying dry humor, humility, and genuine concern for the well-being of others.

The book makes three main arguments. The first is that “pollution is best understood as the violence of colonial land relations rather than [as] environmental damage, which is a symptom of violence”; this violence may be reproduced “even through well-intentioned environmental science and activism.” Looking temporally upstream, Liboiron asks, “What allowed such complete capture of environmental regulation by industry to exist from the earliest moments of the twentieth century?” Looking upstream reveals that plastics were not always regarded as pollution, and that there once were multiple definitions of pollution that differed from the definition that has since been accepted by environmental scientists. In order to be somewhat protected from a pollutant, people are now required to demonstrate that levels of it have crossed some threshold of harm. And defining harm as Streeter and Phelps did—as the point at which a river can no longer assimilate waste—leaves out other definitions of pollution that include such variables as “smells, fish health, water colour, or whether the river was nice to swim in, all of which had been used to define pollution in the past.”

Science’s colonial origins have resulted in assumptions that Liboiron overturns—in particular, assumptions about resource use, the separation of continuous phenomena into discrete variables, the concept of thresholds in pollution science, and universalism. Universalism is the philosophy that certain truths hold across all times and places. Liboiron notes that the concept of universal truths—unlike the concept of Land—removes ideas from their context, their place, and the relationships to which knowledge producers should be held accountable. By contrast, feminist standpoint theory is a philosophy that prioritizes one’s place and context as important to the knowledge one produces, and Indigenous epistemologies see relationships as central to reality. When it comes to plastics pollution, the concept of thresholds breaks down—the idea that Streeter and Phelps took as so universal that it became baked into environmental policy was not, in fact, universal. Endocrine disruptors from plastics do not follow the sigmoid curves that Streeter and Phelps used to define thresholds for organic waste.

To view Land as a Resource is a “colonial understanding” of Nature, Liboiron writes, in which

(certain) humans can protect, extend, augment, better, use, preserve, destroy, interrupt, and/or capitalize on robust-within-limits Nature. . . . Resources refer to unidirectional relations where aspects of land are useful to particular . . . ends. In this unidirectional relation, value flows in one direction, from the Resource to the user, rather than being reciprocal.

Liboiron notes that the concept of resource use pervades not only environmental policy and field methods but also current scholarly practices across academia. Even the way one cites and acknowledges others’ contributions to one’s research can end up treating knowledge, research, and people as Resources, thereby reproducing colonialism.

The book’s second main argument is that environmental science can be done with different, anticolonial Land relations, using specific, place-based methods that attend to obligations. Examples abound when one starts looking for them. In the second chapter, Liboiron dwells on the fact that land relations vary based on context and scale. They make important points about how to think through contradictions—for example, not all pollution is necessarily colonial, and sometimes plastics can be considered Land. Navigating these contradictions requires attention to scale and land relations.

The book’s final argument is that “methodologies—whether scientific, writerly, readerly, or otherwise—are always already part of Land relations and thus are a key site in which to enact good relations (sometimes called ethics).” The third and final chapter provides guidance for scientists who do not want their good intentions to result in colonial violence; it lays out “a framework of compromise to describe some ways to ethically maneuver the uneven power relations of dominant and anticolonial science.” The entire book builds to the conclusion that “anticolonial science uses science against universalism, separation, domination, and colonization.”

This third chapter is where Liboiron imparts lessons learned by telling stories about the ethical dilemmas that they and other members of CLEAR (the Civic Laboratory for Environmental Action Research) have faced when resisting the currents of continued colonialism. (For more on CLEAR’s work, see “How Climate Science Could Lead to Action,” January–February 2020.) CLEAR is an interdisciplinary collective of researchers, and much of the lab’s work involves dissecting fish guts to look for plastic remnants. It is refreshing to read of the thoughtfulness lab members bring to a discussion of statistical outliers that represent once-living things; of their unusual attentiveness to the waste the lab produces; of their inclusion of Indigenous people and local fishers in the review process; and of their consideration of researchers’ emotions as an important part of recording data that can influence knowledge production (a practice the lab adopted after reading Data Feminism, a book reviewed by Kaitlin Stack Whitney in the January–February issue).”

Pollution Is Colonialism provides clarity by asking the following practical question: “How will we [scientists] work against scientific premises that separate humans from Nature, that envision natural relations as universal, and that assume access to Indigenous Land, especially when so much of our scientific training has primed us to reproduce those things?” Even though Liboiron often takes a casual tone, using humor and real-life stories, Pollution Is Colonialism is scholarly work with dense and thought-provoking prose that uses jargon from Indigenous studies, science and technology studies, statistics, and environmental science. Liboiron takes great care in defining words such as colonialism, decolonization, anticolonial, capitalism, Land, Resource, universalism, accountability, obligation, and more—to make sure that people, including settlers like me, can understand precisely what is meant in a discursive space where misunderstandings tend to run rampant.

Despite the perceptive criticisms of science offered by Liboiron, a love for science and scholarship are apparent throughout the book. The author’s enthusiasm for nerding out on the details of field, analytical, and review methods is contagious. I predict that it will inspire pragmatic yet profoundly ethical action during a time of dire news and institutional soul-searching.

Untangling and resisting the Gordian knot of justifications, manipulations, and traditions that enable colonialism takes hard work and humility. I am grateful that Liboiron has written a primer to get us all started. It is rare that I read a book that so fundamentally shakes up my thinking.

Related articles:

- “The Colonial Origins of Tropical Field Stations,” July–August 2017.

- “How Endocrine Disruptors Affect Menstruation,” September–October 2021.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.