STEM Books for Adult and Young Adult Readers 2017

By Dianne Timblin

Engaging reads and beautiful books for STEM enthusiasts

December 23, 2017

Science Culture Art Biology Communications Environment Mathematics Physics Review Scientists Nightstand

Whether you're seeking gifts for the STEM enthusiasts in your life or pondering how you might use those bookstore gift cards you've been wishing for, we've got lots of ideas to share. There's a book (or two) here that should appeal to folks who love to dig into physics and cosmology, formulas and equations, flora and fauna, and much more.

Incidentally, this year we've combined our recommendations for adults and young adults. We think any of the titles here would be welcomed by adult readers—young, old, or somewhere in between. That said, young adults with a general interest in science, engineering, and technology may especially enjoy Apollo 8, The Art of Sound, Audubon, Heretics!, On Trails, The Paper Zoo, Psychology, and We Have No Idea. (If you're looking for books for younger readers, you can find our latest recommendations here.)

Apollo 8: The Thrilling Story of the First Mission to the Moon. Jeffrey Kluger. Henry Holt, 2017. $30.

In this gripping read, Jeffrey Kluger—who coauthored Apollo 13 with astronaut and American hero James Lovell—tells the story of the Apollo 8 mission. The mission's goals and timeline were hair-raising, in no small part because the crew training for the Apollo 9 mission were bumped up to Apollo 8, with only 16 weeks to prepare. Furthermore, the mission was expanded, and how. Instead of remaining in Earth's orbit as originally planned, the astronauts who boarded Apollo 8 were the first to orbit the Moon. Even though readers have the benefit of knowing that the crew returned safely after a successful mission, Kluger's deft storytelling and detailed depiction of everything from quietly fretful family members to alarming last-minute aircraft fixes make it abundantly clear that during that moment in 1968 nothing was certain. The Apollo 8 mission was the first to provide astronauts a view of the Moon's dark side, and it enabled us to see the first, now iconic, photographs of our planet as viewed from the Moon. It's also the mission that Lovell himself, as he noted during a lecture at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill last fall, recalls with the most pride. Viewed through Kluger's lens, it's easy to see why.

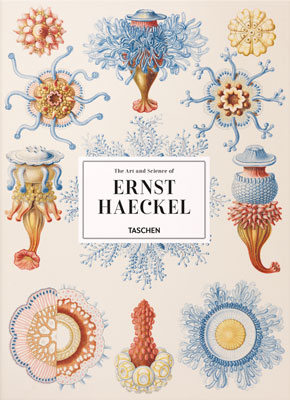

The Art and Science of Ernst Haeckel. Rainer Willmann and Julia Voss. Taschen, 2017. $200.

This glorious book is one of my absolute favorites this year. A trilingual edition, it presents essays on the life and work of naturalist, zoologist, and artist Ernst Haeckel, whose research and illustrations as well as his devotion to Darwin's theories have had a powerful and lasting effect on science. It also reproduces, beautifully, 450 of Haeckel's artworks from several key publications, including Monograph on the Radiolaria; Atlas of Calcareous Sponges; Arabian Corals; Monograph on the Medusae; and his masterwork, Art Forms in Nature. And publisher Taschen (which has released several excellent books this year focusing on the intersection of science and the arts) was not playing around when planning and designing this title: At 704 pages and large enough to dwarf all but the biggest coffee tables, it's a substantial tome. The book is so heavy that it comes in its own handled carrying case, a touch that's somewhere between thoughtful and necessary. There's more to love about this book than I can detail here, but I especially appreciated Julia Voss's essay, "Ernst Haeckel and the Evolution of Modern Art." I was delighted to see her discussion of the collaborative conversations that took place between Haeckel and master biological model-makers Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka, father-and-son glass artists. (More about the Blaschkas and some of the species they modeled in glass here.) Especially transfixing are photographs and design illustrations for art nouveau chandeliers, one for the Oceanographic Museum of Monaco and another for the Amsterdam Stock Exchange, that were directly inspired by Haeckel's scientific drawings. Haeckel was far from perfect (he extrapolated racial differences based on Darwin's theories that were wretchedly wrongheaded); nonetheless, his influence on art and the natural sciences remains profound, and his stunning artworks continue to stand the test of time.

The Art of Sound: A Visual History for Audiophiles. Terry Burrows. Thames and Hudson, 2017. $50.

Blending matter-of-fact discussion of audio technology with incisive takes on pop culture, The Art of Sound is a visual and readerly treat. The book is divided into chapters representing four eras of audio evolution: acoustic, electric, magnetic, and digital. Each chapter opens with a timeline anchoring the era, followed by a lucid essay by author Terry Burrows, a musician and producer as well as a writer who specializes in music history. Then comes a generous array of gorgeous photographs, most of them taken by Simon Pask of items from the EMI archives. Sections of patent drawings punctuate the transitions between chapters, and it’s easy to get pleasantly lost in their details as you note changes over the decades, especially the gradual shift from acoustic era's elegant mechanics to the intricate circuitry of digital-era devices. For more about this book, see our discussion of The Art of Sound in the group review "Sumptuous Science" (Nov–Dec 2017 issue).

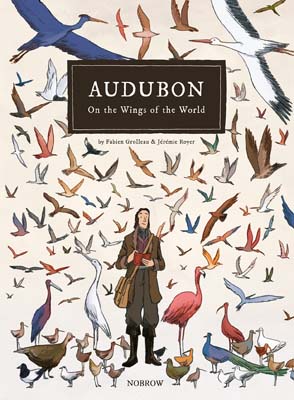

Audubon: On the Wings of the World. Written by Fabien Grolleau; illustrated by Jérémie Royer. Nobrow, 2017. $22.95.

Those who have even a passing interest in famed naturalist, ornithologist, and zoological illustrator John James Audubon, best known for his masterpiece The Birds of America, will find themselves entranced by this graphic-novel treatment of his field work and artistry. The story focuses more on Audubon's experiences, particularly in the natural world, as he lived them and less on technical detail, but it's evident in Audubon that he is as much a naturalist as an artist, even though at the time some viewed the intersection of those abilities with skepticism. Yet he is just as dogged and perfectionistic in learning about his subjects as he is in painting them—journeying, for example, to a distant forest in all seasons and conditions, returning to a particular sycamore to better understand the migration schedule of a particular flock of swallows that nested there, marking some with ribbons to track them from year to year. Writer Fabien Grolleau and illustrator Jérémie Royer do a wonderful job of capturing Audubon's awe for the natural world, a feeling that drove and inspired him to the point of obsession. They also remind us why, for early-19th-century naturalists in North America—a land populated with vibrant pileated woodpeckers, coral-pink-hued flamingos, and passenger pigeon migrations so dense that flocks dimmed the Sun's light for days—obsession was perhaps the most logical response.

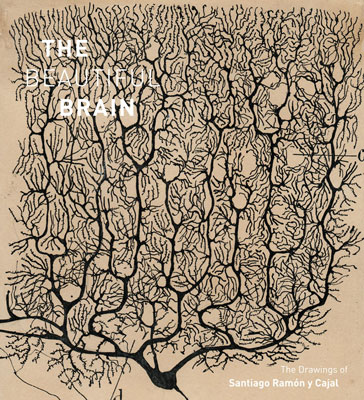

The Beautiful Brain: The Drawings of Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Edited by Eric A. Newman, Alfonso Araque, and Janet M. Dubinsky. Abrams, 2017. $40.

Although he's credited as a founder of the field of neuroscience, Spanish neuroanatomist Santiago Ramón y Cajal isn’t a household name. Perhaps he should be. He improved on Italian histologist Camillo Golgi's method of staining nerve tissue, which had for the first time made nerve cells stand out distinctly from other cells, making the method more practical and its results more reliable, paving the way for close observation and study. Soon he discovered that the brain is composed of nerve cells, named neurons by German anatomist Heinrich Wilhelm Gottfried von Waldeyer-Hartz, a colleague and friend who promoted Cajal's work in Germany, then a hotbed of microanatomy studies. In 1906, Cajal and Golgi shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their groundbreaking studies. For all of his success in neuroscientific research, Cajal had only entered medicine at the urging of his father, who was a doctor. He saw himself first as an artist. Through his work in microanatomy, however, he was able to bring the two fields together, and his meticulous drawings of cell structures are simply beautiful. This is art of the highest scientific order, but make no mistake—as art, it stands on its own. Cajal's exquisite tracings of microscopic tissue structures help the viewer envision their workings. At the same time, they inspire wonder and spark curiosity—aesthetic and scientific. (To read more about The Beautiful Brain, check out the full review. It includes a gallery of Cajal's drawings from the book.)

Foolproof, and Other Mathematical Meditations. Brian Hayes. MIT Press, 2017. $24.95.

If you're a long-time reader of American Scientist, you're already familiar with the author of Foolproof: Brian Hayes, a former editor of the magazine who authored its Computing Science column for more than two decades. In his latest book, he invites readers along for some rousing adventures in mathematics. Sometimes this involves zooming backward in time—for example, to discuss a legendary formula attributed to an 18th-century schoolboy who later became well- and widely known: mathematical genius Carl Friedrich Gauss. Other times, Hayes considers topics that are strikingly of the moment. This is a refreshing read that opens up new ways of thinking about mathematics. For more about Foolproof, check out our conversation with Hayes about the book.

Henry David Thoreau: A Life. Laura Dassow Walls. University of Chicago Press, 2017. $35.

Walls focuses her biography on Thoreau as a writer, an approach that allows her to engage nimbly with her subject’s many facets, and Thoreau the naturalist features prominently. Beautifully written, this is a substantial volume in which every page feels essential. You won’t want to put it down. (To read author Laura Dassow Walls's thoughts about Thoreau as a scientist, as well as the importance of viewing his body of work through the lens of the geological and natural history of his region, check out "Thoreau as Naturalist." For more Thoreau-related reading suggestions, see "Recommended Reading: On Thoreau, Science, and Culture.")

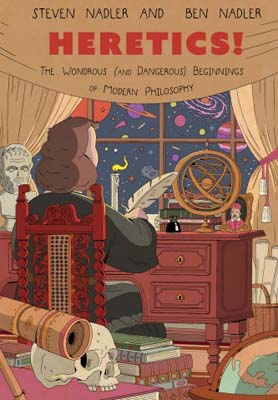

Heretics! The Wondrous (and Dangerous) Beginnings of Modern Philosophy. Steven Nadler and Ben Nadler. Princeton University Press, 2017. $22.95.

In Heretics!, philosophy professor Steven Nadler and his son, illustrator Ben Nadler, remind readers of the abiding connection between 17th-century natural philosophers (or as we call them today, scientists) and our contemporary view of the sciences and their intersections with other fields. This entertaining and thoughtful account of the European philosophical scene circa 1600–1703 presents a parade of philosophers—from Galileo Galilei, Francis Bacon, and René Descartes to Blaise Pascal, Robert Boyle, and Isaac Newton—as they exchange ideas, navigate alliances, and engage in scholarly feuds. The Nadlers present this twisty and entertaining narrative in the style of a graphic novel, and it's a highly successful approach. Discussing and contextualizing a century’s worth of thought about the properties and interactions of the cosmos, God, the human mind, the human body, and natural phenomena is no small task. But through this vibrant, lively book, author and illustrator both make their topic highly engaging as well as sufficiently complex. (If you'd like to read more about this title, check out the full review.)

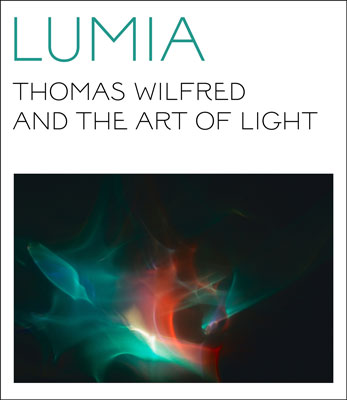

Lumia: Thomas Wilfred and the Art of Light. Keely Orgeman. Yale University Art Gallery and Yale University Press, 2017. $45.

The release of Lumia coincided with the opening of an exhibition of Thomas Wilfred’s work at the Yale University Art Gallery, where author Keely Orgeman curates American artwork. Lumia is the first book devoted to Wilfred’s work in 40 years, and it aims to introduce this pioneer of light-based artwork to new generations. (His name for the medium, lumia, never quite caught on.) His experiments with manipulating light into art began in 1919, which meant that it was necessary for him to invent many of the technologies that made his work possible. Early in his career, he focused on producing vibrant, abstract performance artworks composed of vividly hued, sinuous light forms that call to mind the aurora borealis, and that style of projecting light remained his signature throughout his career. Lumia makes it clear why Wilfred deserves a spot in the 20th-century canon, and Keely does a terrific job discussing not only the artistic merits of the work, but also its significance in the context of the technology and physics of the time. A panel of experts have contributed specialized essays—on Wilfred’s art in a postwar context, on the process of conserving the works’ mechanical structures, and on the artist’s legacy—that make for fascinating reading as well. The still images of Wilfred’s works do not disappoint, and photos of the equipment he developed and some of his conceptual drawings are helpful and revealing. Read more about Lumia in the group review "Sumptuous Science" (Nov–Dec 2017 issue).

On Trails: An Exploration. Robert Moor. Simon and Schuster, 2016. $25.

On Trails is environmental journalist Robert Moor’s first book, and it displays a quality I find essential to exemplary writing: obsession. The subject of trails has long had him in its grip, and his enthusiasm for it is both palpable and contagious. Moor opens the book by examining the first known trails on the planet: fossilized tracks made in the seafloor by Ediacaran biota—simple, soft-bodied creatures categorized as the earliest known complex multicellular organisms and believed to be the first creatures capable of locomotion. A sequence of chapters then focus on trails made by six-legged fauna, four-legged fauna, and two-legged fauna; in each case, Moor considers how these trails are made, how they function and evolve, and how they affect interactions within and among species. In the case of human-made trails, he also discusses how the purposes and priorities of trail makers result in different kinds of trails. Although Moor remains scrupulously focused on his subject, On Trails is nonetheless steeped in philosophy, literature, and, notably, the sciences. Readers who expect geography, geology, sociology, anthropology, and the natural sciences to feature prominently in this volume won’t be disappointed. Happily, the sureness of Moor’s narrative voice pieces these disparate elements together with apparent ease. (To read more about On Trails, check out the full review.)

Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Past. Zoe Lescaze. Taschen, 2017. $100.

Paging through Paleoart is like taking a time- and space-bending, multicentury global tour of natural history museums and amusement venues and getting to compare what scientists and artists from era to era believed prehistoric creatures must have looked like. Author Zoe Lescaze, whose background includes art history and archaeological illustration, proves an intrepid guide through the scientific and artistic eras, and her lovely writing and good humor make the text a pleasure to read. This is a huge book—in size and in stature. For more, check out the discussion of Paleoart in our group review "Sumptuous Science" (Nov–Dec 2017 issue).

The Paper Zoo: Five Hundred Years of Animals in Art. Charlotte Sleigh. University of Chicago Press, 2017. $45.

Historian Charlotte Sleigh’s book The Paper Zoo, taps into the British Museum’s rich collection to explore and contextualize five centuries of zoological illustration. In addition to their utility in the classroom, Sleigh notes that zoological illustrations helped far-flung naturalists keep up with discoveries made in distant corners of the world. Further, the very act of drawing proved useful to some scholars as they strove to prove hypotheses; later on, sharing the finished illustration could lend additional credence to the research.The book’s sections on exotic animals (in other words, those not native to Great Britain) and on “paradoxical” creatures (that is, fauna such as flying fish and stick insects that appeared to defy taxonomic boundaries) are balanced by chapters on domestic animals and on Great Britain’s native species. The pleasures of these chapters, although less intense, are abundant and not to be overlooked. Readers who interested in the intersections of zoology, art, and culture will find The Paper Zoo makes a fine addition to their personal science libraries. (To read more about The Paper Zoo, check out the full review.)

The Sun. Leon Golub and Jay M. Pasachoff. Reaktion Books and the Science Museum of London, 2017. $40.

Our Solar System's own yellow dwarf star has been variously worshiped and taken for granted by the humans who depend on it. All the while, our scientific understanding of the Sun has increased exponentially, and Smithsonian astrophysicist Leon Golub and Williams College astronomer Jay M. Pasachoff fill readers in on what we know and how we came to know it. From the spots on its surface to the physics at its core, this tour of the Sun is intriguing, accessible, and technically detailed. To read an excerpt from The Sun, about the nature of the corona visible during a total eclipse, check out "In the Shadow of the Moon" (Oct–Sep 2017 issue).

We Have No Idea: A Guide to the Unknown Universe. Jorge Cham and Daniel Whiteson. Riverhead, 2017. $28.

Most STEM-related books focus on what we know, thanks to years of research. In contrast, We Have No Idea focuses on what lies, cosmically, beyond those frontiers. Jorge Cham, former roboticist and creator of the fabulous comic Piled Higher and Deeper (aka PHD Comics), teamed up with particle physicist Daniel Whiteson to pen this deeply engaging exploration of ongoing cosmological research. Chapters that roam the universe's mysteries—such as "What Is Dark Energy?," "Why Is Gravity So Different from the Other Forces?," and "Why Are We Made of Matter, Not Antimatter?"—are interspersed with Cham's comic drawings, which serve to entertain while illustrating scientific concepts. For instance, amid a discussion about how, in an expanding universe, objects can become more distant from each other without actually moving, cartoon versions of Cham and Whiteson face each other within a model universe. Paired drawings demonstrate the expansion, after which Cham observes, wide-eyed, "I feel like we're drifting apart." We Have No Idea illuminates why everything we don't know—and are striving to learn—about the universe is at least as fascinating as everything we know.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.