To Boldly Know: Why Scientists Should Care About Science Fiction

By Kristen Koopman

Science fiction dwells at the intersection of science and the broader society in which it operates.

December 17, 2019

Macroscope Art Psychology Technology

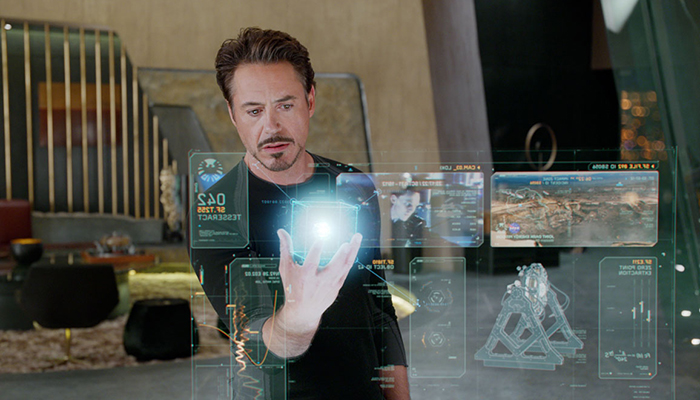

It's hard to argue about the impact of popular culture on technology when people like Elon Musk do things like tweet about how something he saw in Iron Man made him make something in real life.

But for the billions of us who aren't Elon Musk, it's worth asking: Why should we care about science fiction if we don't have the means to make it an immediate reality?

First, science fiction is everywhere. As a genre, it has an increasing grip on popular culture; 8 of the top 10 highest-grossing films of all time are science fiction, and genre television shows such as Game of Thrones and Westworld have become must-watch TV. As much as we might hate to admit it, the fact of the matter is, more people have seen Iron Man than will ever read any of our journal articles. San Diego Comic Con had 130,000 attendees in 2018; the American Physical Society that year consisted of fewer than half as many members. Science fiction just has reach.

The Avengers, Robert Downey Jr. (as Tony Stark), 2012, © Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures/courtesy Everett Collection

Second, science fiction affects the way that people talk about and understand science and technology. Sometimes this can be beneficial to scientists when outlandish claims are dismissed as science fiction, emphasizing that actual science is something else. But sometimes real science can be dismissed as science fiction, too, such as the inevitable comparisons of scientific researchers to Dr. Frankenstein in debates in the 1990s over embryo research. Even more directly, science fiction can affect the distribution of scientific funding: Paleontologists and natural science museums capitalized on the popularity of Jurassic Park, and scientists studying near-Earth objects (and potential impact threats) drew on apocalyptic narratives such as Deep Impact and Armageddon to make the importance of their work clear and visceral.

Third, in a less intense version of the Elon Musk tweet above, the portrayal of new technologies can spark in audiences a desire to see those technologies made real and prepare audiences to use them once they exist. There's an entire role in movie production devoted to that process: the science consultant, whose job is to oversee and critique (although not necessarily with any real power over production) the use of science in films.

Fourth, science can directly inspire specific technologies or scientific concepts. Although I have yet to find a single comprehensive study of scientists’ attitudes toward science fiction or the success rate of science fiction in predicting scientific or technological advances (and if you have one, absolutely send it my way), there are certainly isolated cases and anecdotes of both. The archetypical example is Arthur C. Clarke's role in coming up with the idea of the geosynchronous communications satellite. However, one surprisingly deeply researched area of overlap is the relationship between Star Trek’s Computer (which responds to verbal commands and queries, typically in Majel Barrett-Roddenberry's voice) and the field of human-computer interaction.

Lastly, I have a personal example of the kind of reach and impact science fiction can have for scientists. The first unit of my 10th-grade chemistry class began with a clip from Raiders of the Lost Ark, when Indiana Jones attempts to measure out an equal volume of sand to replace a golden idol on the plinth. This replacement sets off an iconic trap that has him scrambling away from a giant, rolling boulder, idol in hand. Then a sudden chasm appears before him, with his guide-slash-assistant on the other side, insisting that Indy throw him the idol before he'll return the whip that will see him safely across. Indy throws the idol; his guide deserts him.

Raiders of the Lost Ark, Harrison Ford as Indiana Jones, 1981. © Paramount/courtesy Everett Collection

After watching the clip, we did a series of experiments to determine the different densities of sand and gold to estimate the weight of Indy's bag of sand (about 3 pounds or 1.4 kilograms) versus the weight of the idol (about 45 pounds or 20 kilograms). And then, because my chemistry teacher was also the ultimate Frisbee coach and therefore loved causing chaos, we took a 45-pound weight outside and tried to chuck it about the width of the chasm.

This story is what I think of every time I hear someone criticize the use of science fiction or any media in the classroom. It’s been more than a decade and I still remember how much a liter of gold weighs, and every time I think about density I can hear the clank of that 45-pound weight on the sidewalk. Chemistry was never my favorite subject, and today I couldn't titrate my way out of a paper bag, but the fact of the matter is that I remember that lesson because I care about Indiana Jones. I remember Indiana Jones, so I remember density. It's a useful mnemonic, and it has reach.

How many people have watched The Avengers and wondered about gamma radiation when they saw the Hulk? How many people watched Iron Man and ended up down the rabbit hole of “We're X Years Away from a Functioning Exosuit” thinkpieces? How many people watched Avatar and pulled up the Wikipedia article on exoplanets? How many people saw Jurassic Park and went to the nearest natural history museum, and how many saw Armageddon and felt just a little bit better about the amount of money NASA spends on monitoring near-Earth objects?

I am not suggesting that science fiction can only benefit scientists. Jurassic Park spurred natural history museum exhibits, but it also made a fairly critical point: “Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn't stop to think if they should.” Science fiction can also serve as a way to talk about the bigger patterns of science and how they relate to society, beyond the details of a specific project. And as my earlier examples show, people do talk that way.

So here's the vicious truth about how science fiction works: It reaches more people than will ever read any scientist’s papers. And that, if for no other reason, is why scientists should care.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.