This Article From Issue

September-October 2019

Volume 107, Number 5

Page 312

UNRULY WATERS: How Rains, Rivers, Coasts, and Seas Have Shaped Asia’s History. Sunil Amrith. 397 pp. Basic Books, 2018. $35.

Current anxieties over global warming have unsettled our previous understanding of nature (the nonhuman world). No longer viewed as predictable, passive, and within human control, nature is today described as being vengeful as it ferociously unravels in extreme weather events, heat waves, melting glaciers, and rising sea levels. In Unruly Waters: How Rains, Rivers, Coasts, and Seas Have Shaped Asia’s History, Sunil Amrith acknowledges this perceptual shift and argues that a fresh current in environmental history is needed to capture within a single frame “not only how climate has shaped us, but how we have affected the climate.” His effort, in essence, is to encourage explorations of environmental history that respond meaningfully to the politics of climate change.

Unruly Waters, at heart, contends that understanding Asia’s contemporary vulnerabilities to climate change requires a focus on the different histories of “water control” that have been crucial in shaping the continent. In this fresh and provocative telling, we are thus given a sweeping account of “how the schemes of empire builders, the visions of freedom fighters, the designs of engineers—and the cumulative, dispersed actions of hundreds of millions of people across generations—have transformed Asia’s waters over the past two hundred years.”

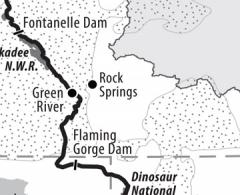

From Unruly Waters.

Although the book is pitched as a continental-level inquiry, Amrith puts India at the heart of the story. Much of the discussion, in fact, draws upon India’s troubled encounters with British colonialism and the country’s equally trying challenges with regard to national development from the midpoint of the 20th century onward. The environments put under the lens in Unruly Waters involve horizontal terrains—coasts, rivers, and seas. However, their animation and dynamism are traced to the enormous infusion and influence of the vertical atmosphere in the form of the Asian monsoon, the weather system of seasonal prevailing winds that distributes the seasonal wet and dry phases. And linking the horizontal and the vertical is water, which as vapor, precipitation, and flows connects the two domains and provides Amrith with the contexts for reconsidering Asia’s varied environmental entanglements and encounters. But water, we are nonetheless cautioned, is more than a resource. Water is also an ideological force, capable of generating anxiety and social distress; in addition, it performs as a “sampling device” by which ruling ambitions and technological prowess can be regularly gauged.

Unruly Waters begins by detailing the British Empire’s attempts to come to grips with the Indian monsoon. Over the course of the 19th century, British authorities realized that the monsoon brought forward a contradictory reality: Although the rains were central to agriculture and to all life on the subcontinent, the monsoon itself was too capricious and irregular to be depended upon. Consequently, colonial officials found themselves not only monitoring the cropping cycle in India but also grappling with recurring destruction from rampaging floods, searing droughts, and deadly famines. It thus appeared obvious to many a colonial engineer and administrator that river control was the only way out of the cycle of devastation.

Amrith gives us a colorful account of the colonial quest for perennial irrigation in India. He describes a collage of events, causes, and initiatives: the spectacular efforts of men such as Arthur Cotton (the engineer who dammed the Godavari River) and Proby Cautley (the chief architect of the Ganges Canal); technical miscalculations, financial failure, waterlogging, salinity, and the unintended formation of malarial swamps; and the steady expansion of monocropping and commercial agriculture. But attempts to outmaneuver monsoonal failure through assured irrigation were not always adequate. In time, colonial authorities were equally compelled to warm up to the view that the railways would be needed to outrun famines by moving grains and other food supplies into distressed tracts. The demand for such infrastructure, however, rested on the questionable premise that hunger and food shortages in colonial India were entirely the doings of the fickle monsoons, when in fact more of the blame should have been placed upon heartless, exploitative, and unjust colonial policies.

Ironically, as Unruly Waters points out, if anxieties over the failing rains and fears of famine drove British canal and transport projects in the 19th century, it was the very same variant of apprehensions about a whimsical monsoon and food insecurities that fueled the nation-building ambitions of nationalist leaders in Asia during the decolonization phase. These newly installed governments, Amrith suggests, pushed for industrialization, intensive agriculture, and large dam construction because they continued to be haunted, in large measure, by the previous colonial nervousness about the monsoons. According to Amrith, the enthusiasm for big-dam construction by nationalist engineers such as Mokshagundam Visvesvaraya (1860–1962) in India and Li Yizhi (1882–1938) in China could be traced to such colonial anxieties. In 1954— convinced that “the control of water was a source of power; its absence, a source of enduring exclusion”—the Indian government dispatched two of its finest hydraulic engineers, Kanwar Sain and K. L. Rao, to China. The strong hope was that these Indian engineers could document and learn from China’s ambitious water projects and hydrological experiments. From the 1970s, however, both countries further ramped up the supply of water for irrigation (to meet their need for agricultural growth) through a frenetic expansion of groundwater mining by means of electric pumps and diesel tube wells.

The “most bitter of ironies,” however, soon followed. The water-fueled pattern of development and the relentless pursuit of intensive agriculture in Asia began to sour into an environmental crisis. Increasingly, as the decades unfolded after the 1980s, talk about using industrialization and economic growth to overcome the monsoon was giving way instead to the realization that the monsoon itself had probably begun to be destabilized. But understanding the monsoon as a weather system and not simply as a rainfall event required a shift from emphasizing river control to monitoring the coasts.

Back in the 19th century, when colonial officials had been trying to establish links between famines and meteorology, they were also busy investigating cyclonic storms that were regularly battering the eastern coast of India. Here, Unruly Waters ties together otherwise unconnected threads by tracking how these investigations of cyclonic storms led the investigators to study the monsoon as a specific climatic phenomenon. In part, as Amrith points out, the effort was to develop early warning systems that would allow the evacuation of populations who were directly in the storm’s path. These studies on the coasts, however, were soon offering clues for deciphering Asia’s complex climate regime.

The first official meteorologist of British India, Henry Francis Blanford, who rose to prominence with his studies of the Calcutta cyclone of 1864, sought to explain climate behavior by following links between “land winds” and rainfall. Blanford defined the monsoon as a “self-contained system” driven by temperature contrasts between land and water. His successor as director of the Indian Meteorological Office, John Eliot, went on to outline an even larger canvas. For Eliot, the “aqueous atmosphere” involved connections among the Himalayan rivers, clouds, ocean winds, and evaporations from the Bay of Bengal. We are also given in Unruly Waters a riveting account of the expansion of the Indian Meteorological Department—the steady rise in the number of observatories across India; the fascinating roles of Elizabeth Isis Pogson (the first woman meteorologist) and Indian meteorologists such as Lala Ruchi Ram Sahni and R. B. Hem Raj; and the interesting ways in which international networks came together to monitor global weather patterns.

By the early years of the 20th century, the collected observational data were substantial enough to enable the breakthrough research of Eliot’s successor, Gilbert Thomas Walker, who discovered the Southern Oscillation, which established linkages between the Pacific and Indian Oceans through atmospheric pressure. Walker’s findings subsequently became crucial to the work of Jacob Bjerknes—the Norwegian meteorologist who, five decades later, established the influence of the El Niño in global weather events. Subsequent developments in the 1960s in aerial photography and satellite imagery were able to further reveal many more intricacies that made up global weather. For Amrith, the greater understanding of the monsoon’s interconnectedness heralded another telling perceptual shift: from an Asia of empires marked by trade routes to an Asia that can now be grasped as a “vast weather system stretching beyond national boundaries.” The meteorological sciences, in effect, ended up revealing the interconnectedness of Asia’s variegated ecologies. Sadly, despite these incontrovertible scientific grounds for environmental cooperation, states and governments in Asia, according to Amrith, remain unable to “think beyond their borders,” displaying instead an inwardness that continues to “imperil lives and denude the political imagination.”

Amrith’s thoughtful account could, however, have benefited from further discussion of certain points. For instance, several recent studies have shown that floods, especially in eastern India, have not always been viewed as unmitigated disasters. If anything, through a mix of inundation irrigation and wetland cultures, several communities have historically tapped into the annual flooding for benefits such as fertilizing silt and fish. The catastrophic consequences of flooding are not simply the result of the monsoon’s fickle behavior; they are aggravated by policies that disrupt drainage and encourage the settlement of communities in vulnerable zones.

Likewise, the implication that Asian governments could tackle climate change challenges through borderless environmental imaginations strikes me as politically naive. Over the years, several Asian governments have relied on making strong claims for political boundaries to argue against what they consider to be the unfair and unequal imposition upon them of carbon reduction targets by the countries that are historically responsible for heating up the planet.

Unruly Waters is a novel and compelling effort that puts the contemporary politics of climate change directly under the lens of the environmental historian. Moreover, it reaffirms that environmental histories must decisively abandon the nostalgic notion that conservation strategies can return the planet to some pristine environmental moment in its evolutionary past. In a climate-changed world, the preferred mood, Amrith suggests, should be one of melancholy—a sense of loss that urges caution in efforts to achieve planetary health and human flourishing.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.